Michael Laub / Remote Control Productions

The Biography Remix

with Marina Abramovic (2004)

PHOTOGRAPHY / CREDITS / PRESS

"My grandfather Varnava was the patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church. He refused the King's request to unite the Catholic and Orthodox Church. After this, the King's personal doctor put crushed diamonds in his food at dinner. After his violent death my mother joined the communist party."

"My mother told me that when she was pregnant with me, she dreamt that she was giving birth to a huge snake. When she was giving birth, I came out but half of the placenta was still inside her. None of the doctors noticed. Shortly after that, she got an infection and almost died."

CREDITS

Conceived by Marina Abramovic and Michael Laub

Directed by Michael Laub

With Marina Abramovic

Jurriaan Sebastian Löwensteyn – son of Ulay, Viola Yesiltac, Herma Auguste Wittstock, Eun Hye Hwang, Heejung Um, Doreen Uhlig, Matteo Angius

and Marco Bilanzone, Francesca Borromeo, Roberto Cecchini, Maria Giovanna Massari, Beatrice Novelli, Alessandra Roca, Massimo Scarinzi, Antonio Tagliarini, Andrea Valabrega, Emiliano Mazzoli

Singer Raffaella Misti

Additional Music Larry Steinbachek „Ninth Seven 2“

Assistant Director Declan Rooney

Assistant to Marina Abramovic Snezana Golubovic

Technical Director and Video Coordinator Jochen Massar

Light Design Luca Storari

Sound Engineer Alfredo Sebastiano

Stage Manager Ettore Littera

Head Machinist Claudio Petrucci

Machinist Payam Noruzi

Electrician Walter Pizzi

Digital Display Laura Clemens

Technical Coordinator Luigi Grenna

Props & Costumes Marina Schindler

Animal Trainer Daniel Berquini

Executive Producer Fabrizio Grifasi

Production Stefania Lo Giudice, Fabiana Piccioli, Renato Criscuolo

Management Michael Laub / Remote Control Productions Claudine Profitlich

Produced by Romaeuropa Festival 2004

In Cooperation with Teatro Palladium Università Roma Tre

Supported by: the Netherlands Culture Fund, Theater Instituut Nederland and the Embassy of the Netherlands in Rome

PRESS

Jean-Marie Wynants, Le Soir, 13 July 2005

The very fine “Biography Remix” made up for the disappointing premiere of the much-anticipated “Puur” by Wim Vadekeybus. After experiencing a lacklustre performance from Jan Fabre and Groupov, one was hoping that Wim Vandekeybus would reconcile the public with those Belgians some have begun to eye suspiciously. Although “Puur” was not really disappointing, it sometimes seemed a little long, slow and confused.

We are in a future world, so the programme tells us, amidst a society of survivors after some unnamed catastrophe. A film serves to reproduce that period, to recover the fragments of that life in a city where children abound. While it was an interesting idea to project this film onto the wall of the Boulbon carrière, the result unfortunately detracted from the sense, since the reliefs on the foundation distorted the images.

Up on the stage, people are trying to reconstruct, to recover this lost past, are crying for their lost fathers, are celebrating the vigour of their mothers. The bonds between parent and child are frequently mentioned in this piece, which is full of touching moments but all too often excessively drawn out. And that is a pity, because when the action takes off, it is at its most fascinating: bodies carried ever-more inventively, more riskily, more acrobatically – but also the carriers of meaning: the astonishing sequence in which long white batons are hurled from one to another like javelins; women carry their boys with force and with love; bodies balanced on the batons, dressed like pieces of meat set out to dry... One is very aware that the question of paternity, of protecting one’s child is more and more at the centre of events. But the ensemble is lacking cohesion.

Quite the opposite is true of the remarkable “The Biography Remix”. Marina Abramovic has been presenting her “biography” to audiences around the world for several years. In the course of that performance she re-traces her course as a woman and as an artist. For Avignon, she asked Michael

Laub to deliver his own version on the basis of the existing material – hence the title “Remix”. The result is startling and moving in equal measure.

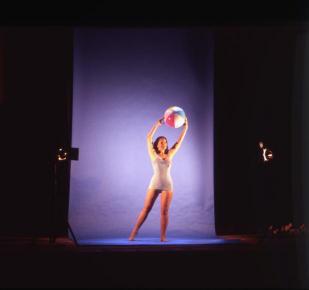

Lasting one hour and a half, the chronological framework is conveyed by an electronic journal on which the great moments of the artist are listed. The projections recall the innumerable performances Abramovic has delivered since the 1960s, supplemented by the presence on stage of a whole band of young men and women, pupils of the artist, who recreate excerpts from the performances.

As the electronic diary indicates, the original performances sometimes lasted anything from six to twelve days. The resumés we now see are only a few seconds, a few minutes, long – but sufficient to grasp the meaning, and the necessity likewise.

Because, confronted with so intimate a mixture of the artist’s personal history and her creations, one learns, as never before, what can motivate a young girl from a family of Yugoslav partisans to play in public with her body, her blood, her image. To scale the Great Wall of China in order to find the man she loves, and then to leave him for good (a bewildering moment). To perch herself three metres away from the sun, a serpent in each hand (splendid opening scene). Or to let herself be smacked over and over again by the waves of the sea, under the eye of a static camera.

Remote from exhibitionism, this magnificent piece directed by Michael Laub launches a fleet of superb images – one does not soon forget the trio of women softly singing, “Bye-bye les larmes, bye-bye la tristesse...”. But above all one remembers authentic emotion, which culminated in the final glimpse of a smile from the artist. It is beautiful, very beautiful; terribly intimate; and perfectly universal.

Antoine de Baecque, Libération, 13 July 2005

A Life of Performances

Marina Abramovic, pioneer of Body Art since the 1970s, movingly and passionately revisits all her pieces.

Marina Abramovic – visual artist of Serbian origin, born in Belgrade in 1946, living and working in Amsterdam – has been a pioneer in the field of Body Art since the early 1970s, along with artists like Gina Pane, Vito Acconci, or Chris Burden. Since then, her performances or videos have been shown just about everywhere, notably at international exhibitions such as the Kassel documenta and the Venice Biennale or, most recently, at the New York Guggenheim, which supplemented the show with a symposium attended by those of her old friends who are still alive, such as Joan Jonas or VALIE EXPORT. As Abramovic wryly puts it, her body is “overexposed”. Because for her it is always a matter of recounting her life, her education, her loves, her desires, her fears, her manner of being well or unwell, through the medium of her own body or those of people close to her, each time confronted by sadness, by exhaustion, by danger, by sex or frustration, by nudity, by crudity.

Pact

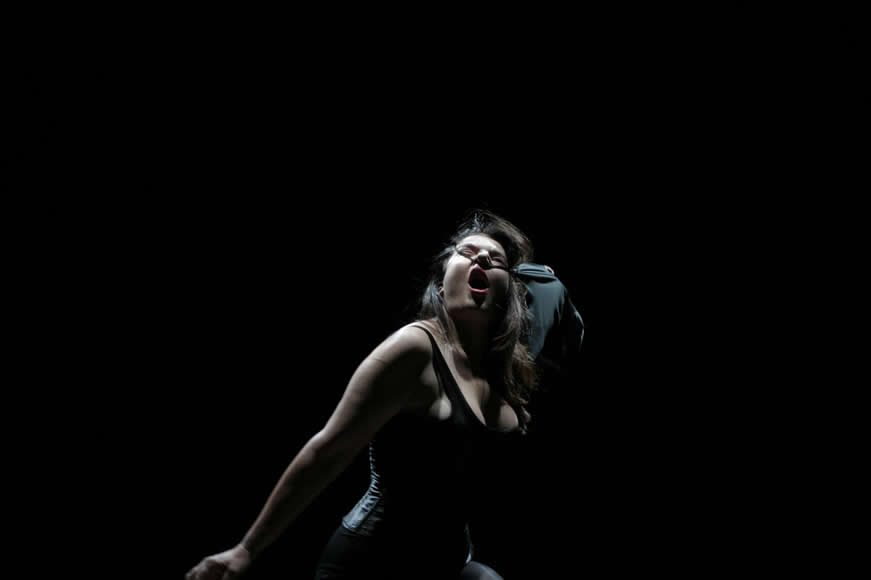

The autobiographical material that she mixes with intensity and ambition has been put in place over the course of two decades: with every exhibition or performance she adds a clause to this biographical pact whereby everything is true, intimate events, described in outline (generally one sentence per year, since 1946), together with the emotions experienced in the flesh. It is necessary to see her as she carves out a star in her lower abdomen using a razor blade, roughly inflicts on herself an incredible series of double slaps, offers herself up to serpents, places her left hand at the mercy of her masterly right as it swiftly stabs a pointed dagger between the fingers of the left, emits howls to end all howls, weeps, or quite simply offers the ghost of a smile to the audience present on the day that coincides with the last line in her narrative: “Avignon, 13 July 2005”.

Maturity

This intimate material is meanwhile coming to maturity. The one-and-a-half-hour spectacle presented in the Benoit-XII hall to an audience hushed with admiration, often on the brink of tears, is on the one hand perfected to an essence intimately and densely populated by the artist, to the point that she is doubled by some fifteen bodies, essentially her students or ex-students, and even the son of the German performance artist Ulay, her earlier companion and partner. In minimal and silent fashion – with the diligence recommended to good pupils – everything restores to the present those performances which stake out the life of Abramovic. Due to the confrontation between the videos projected frontally onto a huge screen and the body which reclaims them in vivo, hic et nunc, and seriously works through them, totally absorbed in the task and the mechanical repetition, this “remix” is generally as disturbing as it is moving.

And then Marina Abramovic herself is there, continuously, so to speak, unparalleled. Her self-description is complex-laden – “big ass, big nose” – but the person is magnificent. She does everything right, the few words she utters are exactly those one wants to hear; the way she says “musique!” before her solo-cum-striptease is simply sublime.

Self-Ridicule

After starting her life naked in an allegorical scene with serpents and concluding it in a severe blue tailored costume, she has passed through all the stages of body and appearance without losing even for a second her natural and flamboyant elegance. And the spirit of the woman! The story of her life is of such acute minimalism that one dreams of somebody with the same faculty of self-ridicule. The memory of a life constantly replayed over its words and its songs, totally defusing the grandiloquence of “notables”. The narcissism of Marina Abramovic is skin-deep, but this art of living permanently with oneself resembles the manner in which she weeps: excessively, to be sure, yet flowing slowly, softly, down her right cheek is merely one solitary, gracious teardrop.

Wiebke Hüster, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 5.10.2004

Extreme-Art Body

Where now Ms. Abramovic? The Biography Remix at the Romaeuropa festival

In the run-up to the premiere of The Biography Remix Italian newspapers described Marina Abramovic as the “Queen of Body Art”, in this way telling Roman audiences what to expect at the theatre: the distilled essence of an artist’s three-decade-long exploration of physical limits. Abramovic, who was born in Belgrade in 1946 to parents who were partisans, has been exposing herself to states of physical and emotional extremity since her first performance in the 1970s, continually shocking and moving audiences in the process. Speaking to this newspaper, she said that torture and death are taboo subjects in the western world, but only those who overcome the fear of suffering are able to see life as a gift. In one of her earliest Action Art pieces, she laid herself down inside a blazing Soviet star, and almost suffocated in the process. She once told a gallery audience to do with her anything they wanted; men ripped off her clothes and harassed her, then somebody put a pistol up to her head – the weapon was knocked out off his hand in the nick of time.

In 2003 Abramovic received a Bessie Award for spending twelve days and nights in the Sean Kelly Gallery in New York, watched by changing audiences. For The House with the Ocean View, she complied with a strict self-imposed regime according to which she lived on water alone, and talking was strictly forbidden.

But how does one transfer to the stage concepts originally devised for galleries, museums or public spaces? And how many hours does one need for a piece devoted to a work whose shortest sections lasted only a few minutes, but whose longest part – The Lovers, The Great Wall Walk – lasted all of three months?

By choosing to collaborate with one of her oldest friends, the choreographer Michael Laub, for the premiere at the “Romaeuropa” festival, Abramovic adopted a new strategy for this latest attempt to transfer her performances to the stage. The director of The Biography Remix began by sifting through the archives. Although he felt it was a challenge to put the “Queen of Body Art” onto the stage, the source of his anxiety was not Abramovic the icon – after all, she had agreed to follow his instructions for portraying her own life – but the objections to be expected from an art world that remembers very well the cathartic effect of earlier performances, for instance those four days during the 1997 Venice Biennial which Abramovic spent sitting on top of a mound of bloody bones, scraping off the flesh and singing laments. The piece Balkan Baroque won a Golden Lion. It is difficult to transport the intensity of such a work into a piece which browses through an artist’s life as if it were the catalogue of a retrospective, and by necessity flicks over some pages and stops at others in order to bring to life the pictures they contain. That is accomplished in exemplary fashion in the opening scene: Wearing only a sun-yellow skirt, Abramovic hangs, as if crucified, in a frame high above the stage. One snake dangles from either of her outstretched arms. Fleshless animal bones are scattered about the stage; two huge dogs gnaw at hunks of meat; and as the growls emanating from the loudspeakers begin to get more threatening, so the snakes become more wary and agitated.

The Biography Remix is the product of the admiration and closeness existing between two people who are polar opposites. On the one hand, that makes the piece an important record of an art-form whose beginnings are in danger of vanishing into the mists of a mythological past. And that probably explains what is felt to be its weaknesses – above all by those who know Laub’s own theatre work and would have expected his interference to be more intrusive, more imaginative. Laub, however, opted to place himself in the service of the piece, and sometimes that meant protecting Abramovic from Abramovic. According to the director, the legendary performance artist is also sentimental, and excessively fond of dramatic appearances. Laub, a strict formalist, detests nothing more than acting. He does his utmost to banish thespian elements from his own unbridled pieces which, influenced by the films of Godard, coax from everyday myths the truth about Bollywood, Indian kathak dance, or Hans Christian Andersen. And so he bows in front of Abramovic only under strict conditions: no acting, no set, and no exclusive performer-audience relationship. Abramovic is not allowed to read aloud the diary entries from each year of her career; instead, the text electronically flows across either side of a stage which remains otherwise empty save for two projection screens for original film footage. The Teatro Palladium, an odd building with ochre-coloured walls and an asymmetrical stage, is presented otherwise unadorned. Many of Abramovic’s art Actions are carried out by her students, for instance Light/Dark – the 20-minute-long exchange of slaps on the face between the artist and Ulay, her partner of many years, who is to be seen in excerpts in a film of 1977, is additionally shortened by being distributed over five couples on the stage (among them Ulay’s son, who bears an uncanny resemblance to his father). Alongside her own work Abramovic is interested today in teaching and in exploring the art-historical definition of Performance, in order to remove the genre from the realm of myth and examine it in terms of usefulness for the future. Michael Laub has taken her one step forward in the objectifying process, but the price she pays is a certain breaking of her own spell.

Steven Henry Madoff, Artforum, October 2005

It was only during the brief rendition of a 1977 performance piece by Marina AbramovicÌ, in which five couples sat and slapped each other’s faces faster and harder over several minutes, that I began to understand the state of contemporary theater.

I was in Avignon for the annual theater festival, which has been held there each summer since 1947 and remains ground zero for the European theater world. The identity crisis under which theater strains, or so its critics say, was in ample evidence. Audiences booed, cursed, and awarded rapturous ovations for the twenty-three works presented, with opinions as diverse as the theatrical styles on view. And where breadth was a point of pride for festival directors Hortense Archambault and Vincent Baudriller—they extolled that the works attested to “the possibility of finding something that could ally with the universal or the sacred to, perhaps, re- enchant the world”—for others it was a failure of focus, a failure to either honor convention or find the truest theatrical form for the times. And then here AbramovicÌ’s couples sat, the sound of flesh hitting flesh growing more disturbing with each percussive slap. This was the opposite of enchantment. Part of Biography Remix, 2004, AbramovicÌ’s multimedia collaboration with Belgian director Michael Laub that serves as a highly selective anthology of her performance art from the last thirty years, the scene was piercingly, almost unbearably, present. It was coated so corrosively with reality that the other works I saw in Avignon were pushed into a different light.

(…)

Symbolic or dreamlike, they packaged the real in theatrical artifice. They replaced reality with its simulation, instead of interacting with it, as AbramovicÌ’s work did. In the broadest terms, as I watched Biography’s old documentary footage of AbramovicÌ and her former partner Ulay screaming at each other until they were hoarse and crying, or the artist exposing her bare belly to an audience as she cut it with a razor blade, or her live performers hitting one another with real, unmediated force, I thought that, despite our daily ingestion of movie and TV special effects in a postliterary, visual world, it isn’t the seduction of the unreal, of Hollywood’s torrent of phantasms, that has changed us, but journalism’s documentary flood of reality. These linear, reportorial narratives—whether in newspapers, in blogs, on TV, in podcasts, on the radio, in streaming video, or in downloads to our cell phones—overwhelm any lingering Baudrillardian thought about the power of the simulacrum, and they contravene the commonplace of aesthetic modernism that the world is most truly represented as fragments. The deluge of these narratives washes over us, infiltrates us, and forms us. They are the dominant way that the world reveals itself today.

John Hooper, The Guardian, 29.09.2004

A matter of life and death

Would you ask a man to aim an arrow at your face? Or slap you as often as he can in 20 minutes? Celebrated artist Marina Abramovic does.John Hooper asks her why

The video, projected on to a screen that fills the entire proscenium arch, shows a naked man. He walks towards the viewer, but there is a rubber cord around his waist, attached to the wall behind him, constantly pulling him back. A woman stands to one side, staring impassively ahead of her. The screen goes up. On the stage behind, a naked man is re-enacting the same, endless sequence while a woman dressed like the one in the video stands nearby. Another video, this time projected on to the rear wall of the stage, shows a woman savagely brushing and combing her hair with a steel brush and comb. It is replaced by images that show her cutting a five-pointed star into her stomach with a razor blade.

We are in the painful, perilous, mesmerising world of performance artist Marina Abramovic. The scenes belong to a work to be premiered today at the Teatro Palladium in Rome during the annual RomaEuropa festival. Part anthology, part biography, part video show, The Biography Remix also points to the direction in which Abramovic hopes to steer performance art, which she helped to pioneer in the 1970s and of which she is today one of the world's leading creators and interpreters.

Abramovic has been putting on representations of her life and work since the late-1980s, when her all-consuming partnership with the man known only as Ulay, the frustrated walker in the video, broke down. They turned their split into an epic performance. Abramovic set off from one end of the Great Wall of China, Ulay from the other, and when they met in the middle, each having walked more than 1,500 miles, they said goodbye. "Afterwards, I was in such pain, mentally and physically, that I could not go back to my own work," said Abramovic. "The only way I could see a solution was if I could take some kind of distance from myself by staging my own life." Since then, she has been creating and performing an updated Biography every four or five years.

Born in 1946 in Belgrade, Abramovic is the daughter of partisans. Her mother joined the Communist party, she says, after her grandfather, the Orthodox Patriarch of Serbia, was murdered on the orders of the king by having ground diamonds put in his food. "He was declared a saint," she adds.

Abramovic had her first exhibition as a painter at 16. In 1968, while other kids were putting flowers in their hair, Abramovic was trying out Russian roulette and discovering Zen Buddhism. Six years later, she left what was then Yugoslavia to settle in Amsterdam. At different times since, she has lived with Tibetan monks and Australian aborigines ("next to the Lake of Disappointment"). At the Venice Biennale in 1997, and to the horror of the Montenegran authorities who had sponsored her, she performed a work entitled Balkan Baroque, which involved her tenderly washing 1,500 bloodied bones. It won her the top award, the Golden Lion.

The last thing you expect her to be is jolly. But she is. She bubbles with bright-eyed enthusiasm and smiles easily. Sitting across the table in a plain white blouse and black skirt, she could be the local building society manager. It is hard to believe that when rehearsals resume, she will be dangling above the stage, bare-breasted and holding a snake in each hand. She has worked with producers on her biographies before, but always retained artistic control. This time, however, she surrendered the last word to the Belgian director and choreographer Michael Laub, even going so far as to sign a contract to that effect. "I didn't ask her to do that," says Laub quickly.

Abramovic's gesture reflects a belief that the way forward for performance art is for works to be reperformed, and even reinterpreted, by artists other than the creator. "I wanted to open up the idea of performance as being like a music score. If you can play Bach hundreds of years after his death and make techno-Bach, why can't you reperform the pieces of an artist of a different generation?"

Next month, she is to put on a series of seven pieces at the Guggenheim in New York. All but one were conceived by other artists from whom Abramovic sought formal permission and instruction. "I wanted to establish some kind of example of how it really should be done," she says. "Until now, there have been a few attempts at reperforming old pieces, by several different artists, but always like a kind of parody, and without asking permission or taking care of the original material."

The Biography Remix is the same idea, but in reverse. It is a Laub creation using Abramovic originals, truly a remix. Laub scrapped the chronological format Abramovic used in the past, and brought in other performers. One moment you are watching the young Abramovic on video, the next Abramovic played by one of her young students, then Abramovic in the flesh.

Trying to make theatre out of a kind of performance art that involves testing the limits of physical and men tal resistance raises special problems. One of Abramovic's most famous performances is Light/Dark, in which she and Ulay slapped each others' faces, increasing in speed till they could go no faster. Laub decided to "serialise" it by using several couples. "The difference between performance art and, say, repertory theatre, is that when Marina and Ulay decided to do something as strictly physical as slapping each other in the face for 20 minutes, they didn't really care if they ended up in hospital the next day, because they were very committed and they didn't have to reproduce the piece," he said. "It's sort of hard as a director to ask these young people to rehearse that." He had managed, he said, "by apologising a lot". And maintaining a stock of ice packs. A book on the making of The Biography Remix includes a photograph of one performer on her back at the end of a rehearsal with ice packs on one knee and the side of her face.

At times, Laub's production transcends Abramovic's performances to make a different creative statement. One of her most powerful works is Rest Energy, from 1980. While she gripped a bow at arm's length with the arrow pointing towards her, Ulay held the arrow to the bowstring with his fingers, then they both leaned backwards till the bowstring was taut and the arrow was aiming straight at her heart. Microphones attached to their chests provided the soundtrack.

"This is a very difficult piece where you really risk your life," said Abramovic. But it is also about love, trust and mutual dependence. And in Laub's production, that comes across even more clearly than the danger, as illuminated digital strips on either side of the couple flash the timeline of their relationship. "1977. We talk to each other in our dreams. 1985. We stop making love."

The effect is redoubled when you know that the man up on the stage holding the arrow, with the power of life and death over Abramovic, is Ulay's son. "I never even knew he existed. He hid it from me," said Abramovic. "He already had one son in Germany by his first wife, and I think he was maybe ashamed that he twice left children behind."

Jurriaan Sebastian Löwensteyn, 32, was working in the theatre, backstage making sets. "Why I am doing this is mostly to explore the past, to explore physically and emo tionally what Ulay and Marina did," he is quoted as saying in the book.

The Biography Remix coincides with several turning points in Abramovic's life. She is giving up teaching next month and leaving Amsterdam after 27 years to divide her non-working time between a flat in Rome, a loft in New York and a house in the Mediterranean. "On Stromboli." I should have guessed. "Stromboli is the last permanently active volcano in Europe," she said, leaning forward intently with her dark eyes flashing. "Every 20 minutes, it's shooting out lava. Every 20 minutes. Black sand. Black beach. Everything black. It's fantastic."