Michael Laub / Remote Control Productions

Burgportraits Vienna (2011)

PHOTOGRAPHY / VIDEO / CREDITS / PRESS

“I walk past the guests who are already present and go into the music room, where I conduct a conversation with the other occupants until Elisabeth II. comes driving past. Apologies: it’s a silent conversation.” (Andreas Dampfhart)

conceived and directed by Michael Laub

based on an idea by Tom Stromberg

Stage Design Michael Laub, Jochen Massar

Costumes Moana Stemberger

Video Astrid Endruweit

Light design Nigel Edwards (Remote Control Productions), Gerald Weilharter (Burgtheater)

Dramaturgy Astrid Endruweit ( Remote Control Productions), Florian Hirsch (Burgtheater)

Assistant Director Ebru Karaca (Remote Control Productions), Madeleine Koenigs and Caroline Welzl (Burgtheater)

with Elisabeth Aref, Claudia Durstberger, Monika Höflinger, Mavie Hörbiger, Petra Morzé, Christiane von Poelnitz, Kinga Walus, Andeas Dampfhart, Thomas Gandon, Heinz Geissbüchler, Karl Heindl, Lion A. Kenechukwu, Wolfgang Klaus, André Meyer, Irene Rottensteiner, Valentin Rottensteiner, Pablo-Miguel Konrad y Ruopp, Michaela Wimmer, Sebastian Wimmer; on video: Maria Happel

and Isolde Friedl, Vitan Bozinovski; Kaoru Asayama, Nahoko Fort-Nishigami, Akiko Heindl, Shoko Kanno, Hiroyo Masumura, Takayo Mucha, Fumie Pichler, Wei Ren, Riho Sakamoto, Tsutaki Takasaki, Yukiko Yamazaki

Stagehands Thomas Herzog, Michael Jackl, Mariano Margarit, Alexander Pirka, Benjamin Reischer

Costume Assistance Luise Ehrenwerth

Stage-Management Klaus von Schwerin

Stage Technique Franz Kriz

Production Management Silvia Platzek

Props Manager Ignazio Atzara, Roland Soyka

Sound Raimund Hornich, Andreas Zohner

Video Technique Michael Schüller, Alexander Söldner

Management Michael Laub/Remote Control Productions Sven Neumann, Claudine Profitlich

with special thanks to Samuel C. Laub

produced by Burgtheater

PRESS

Dorian Waller, Der Standard, 27 March 2011

The Burg As the Sum of Its Parts

Silent grandeur: Christiane von Poelnitz poses wordlessly on the stage while text messages written during the rehearsal period flash up behind her.

Michael Laub applies to Vienna the mosaic concept he developed for Hamburg: In “Burgporträts” the Burgtheater puts its inner life on show, but remains very much of and with itself

Vienna – The stage is about as inviting as a open-fronted photographers’ studio specializing in standard EU-format passport photos. The space normally reserved for metamorphosis and illusion becomes one of voluntary self-revelation in Michael Laub’s “Burg Portraits”. Eighteen Burgtheater employees, from ticket-lady to members of the ensemble, have a limited period of time to reveal something of themselves on the stage.

The Belgian choreographer-director has meanwhile staged in Berlin, Rotterdam, and Istanbul the mosaic portrait concept originally developed with Tom Stromberg for the Hamburg Schauspielhaus in 2001. Boasting five hundred employees, the self-confident Vienna theatre seems predestined to continue the series.

In line with the evening’s theme of self-presentation , several spotlights shine on items of stage equipment prominently scattered about the almost empty stage. In full view of the audience the stage mechanics go about their work, largely confined to lowering or raising the different coloured backdrops suspended like Damoclean toilet rolls over the performers’ heads.

The appearances by company members (including Jungen Burg with a wordless contribution that invites all manner of uncharitable interpretations) amount to highly artificial performances; those by the less familiar behind-the-scenes and front-of-house staff are much more direct. Heinz Geissbüchler, the character who runs the theatre canteen, reaps as many laughs as the bit player Andreas Dampfhart, who revives a nonspeaking part as an ageing elephant. Altogether no small number of extras have a chance to present highlights from their careers in a new light.

“That was Thomas Bernhard,” Claudia Durstberger soberly remarks after her pantomimic revival of the tray-carrying maid in Bernhard’s “Elisabeth II.”, and one suddenly sees the playwright’s work from a different perspective. Other soloists recount episodes in their lives, present their vocal or, as applicable, muscular powers. Common to them all is the relation to the Burgtheater.

That this theatrical reference is thematically preordained need be of no more weight than the question of the extent to which Laub, who shaped the framework and rhythm, also manipulated the delivery. Ultimately, despite moments of solemnity, it is a lighthearted evening that reaps resounding applause and calls of bravo not just for the well-known faces.

Helmut Schödel, Süddeutsche Zeitung, 27 March 2011

Collapsing Balconies

Vienna: Michael Laub stages twenty “Burg Portraits”

Nine years ago, Tom Stromberg invited the director and choreographer Michael Laub to portray Deutsches Schauspielhaus, the Hamburg theatre of which he was then intendant. “Portraits 360 sek.” was the result. Laub then moved into series production: portraits of dancers in Berlin, of residents in Rotterdam, of Turkish women in Istanbul. While the form of such work is sometimes reminiscent of Rimini Protokoll projects, Laub did not want his “Burg Portraits” to explore the Burgtheater in Vienna, peer behind the scenes of Mathias Hartmann’s realm, or produce a back story about a national theatre. His intention was to present twenty individuals chosen from one hundred candidates: people like the ticket-lady, the fireman, the extra, the actress.

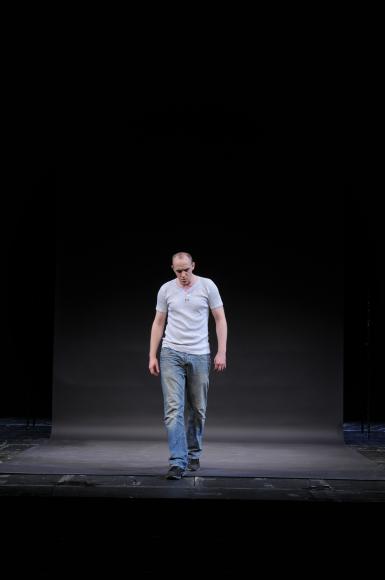

Laub has a keen instinct for people. Certainly, the subjects decide how they want to portray themselves, but the director nudges them in the right direction – and that is to their advantage. The evening is ultimately also a composition blending recitation, acted scenes, and song. More reserved personalities like the ticket-lady who has witnessed more than a thousand performances – “in other words, more than a thousand cheese toasties in the canteen” – alternate with inveterate showmen like the canteen operator who went flying through the back window of the car in front of his motorbike because the attractive Vienna streetwalkers took his mind off the road. “Three weeks in intensive care,” he recalls, “three weeks of plastic surgery” at that time less a medical science than a “workshop for halloween masks”. He found he was on the same wavelength as the celebrities he subsequently served in a bar, and must have been the dream choice to run a theatre canteen. One of the subjects is of almost intimidating physical presence: Lion A. Kenechukwu from Nigeria, European wrestling champion, who likes to be a bodyguard extra.

Laub structures the evening by means of repetitions and one leitmotif: the collapsing balcony in Thomas Bernhard’s “Elisabeth II.”. An extra engaged to conduct whispered background conversations during performances of that play now presents his scenes minus the main players at front of stage – to great comic effect. The same man has notched up a number of wacky roles, including that of an “old, sick, widowed elephant”, which he resurrects for one final and highly professional performance.

The stage set is a photographer’s studio in which stagehands change the backdrops or adjust the lighting. In such a setting the person being portrayed would normally be the photographer’s object, but what Laub provides is creative space for them to develop.

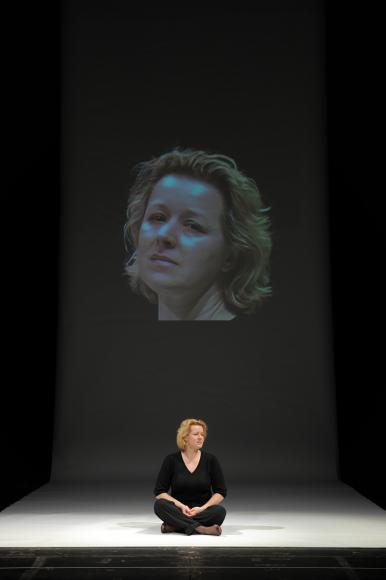

The same leeway is enjoyed by ensemble members like Christiane von Poelnitz, whose text-message correspondence with Laub is projected onto the backdrop. She simply wants to stand there looking strong, says one message. Her wish was fulfilled. She stands there dressed in white, a painterly apparition that could come straight from a fresco, but at the same time a toxic blonde bombshell representing the final victory over the patriarchy.

Mavie Hörbiger was allowed to choose a pose as well. Having unbuttoned her own blouse, she hisses like a cat, as if outraged by improper male advances. Petra Morzé presents herself as a woman abandoned and forlorn. And actor André Meyer comes on strong, daydreaming about action scenes, cutting Rambo grimaces visible high up in the gods as he describes his dream of being a Hollywood icon. Kinga Walus, by contrast, modestly expresses her pleasure that she, an extra, was able to dance with Michael König. The Burgtheater is a dream factory for one and all, including those members of staff Mathias Hartmann describes as “front-of-house”.

The documentary material Laub presents is manipulated; but then documentation of any kind is also manipulation. Here it is a matter of splendidly amusing versions of the authentic. But the director invariably penetrates to the core, sometimes inducing meltdown. As the fireman is about to break into song we notice flames leaping in the background, hear the crackle of fire. The ardour displayed by the people we see on stage appears to be infectious.

Wiebke Hüster, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 29 March 2011

They All Come Back to Life

Michael Laub puts theatre employees on the stage, portraying staff in the Burgtheater, Vienna’s hotbed of intrigue

Vienna, 28 March 2011

Of course, we always suspected that the full-blooded dramatic artists were to be found in the canteen of Vienna’s Burgtheater rather than on the stage. Characters like Heinzi “the canteen’s my stage” Geissbüchler, for one. But for final confirmation we needed Michael Laub, whose “Burg Portraits” premiered at the weekend. Heinzi delivers the most nonchalant performance in a series of self-portraits acted out by various theatre employees. His opening account explains what happened to his nose in the late 1970s: how he raced to Vienna on his motorbike, roared down a street in the red-light district, went sailing through the back window of the car in front of him. If his nose suggests that Austrian cosmetic surgery was a risky business in the early days, then his subsequent decision to run the Burg canteen brought hazards of its own. Such as the injury suffered by the wrist of his right hand at the recent premiere party. After midnight Geissbüchler decided to dance on the table. It broke like treacherous ice under the weight of the budding go-go dancer; hence the splint on Heinzi’s wrist.

A fundamental principle of Michael Laub’s portrait series is that the audience learns how the actors came by their wounds. Laub has been known to cast entire cities for a particular series, as well as theatres. The rehearsal process involves interrogating the subjects, then stringing together their tales in a way that creates a portrait of the individual, but always in relation to theatre, that object of Laub’s obsession. For instance, the ticket-lady (“Billeteurin”) Monika Höflinger, who appears first, tells us she never intended to stay at the Burgtheater so long: but staff who survive the first year stick about. Patrons have meantime seen her face first at the beginning of 1,100 different evenings at the theatre. That adds up to the same number of cheese toasties in Heinzi’s canteen. And to one hundred oil paintings produced in her free time. She then holds up a small painting to the video camera: a blown-up projection shines down from the screen enigmatically.

One of the most modest yet shining stars of the evening appears between the ticket-lady and the landlord of the theatre canteen: Andreas Dampfhart, a bit player at the Burg for the past forty years, and by day a machinist in an offset printing plant, delivers the second of the ninety-minute piece’s nineteen splendid performances. Relishing the opportunity to repeat his finest scenes, he nods to all sides, engages in whispered pantomime conversation with other, now invisible, figures of the Viennese bourgeoisie. He is re-living a production of Thomas Bernhard’s “Elisabeth II.”, a play in which an entire party, save for the host Herrenstein and his servant Richard, go crashing down to the ground along with the dilapidated balcony on which they are gathered. Closing exchange: “They’re probably all dead.” – “No doubt about it.”

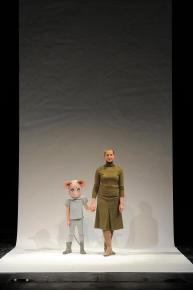

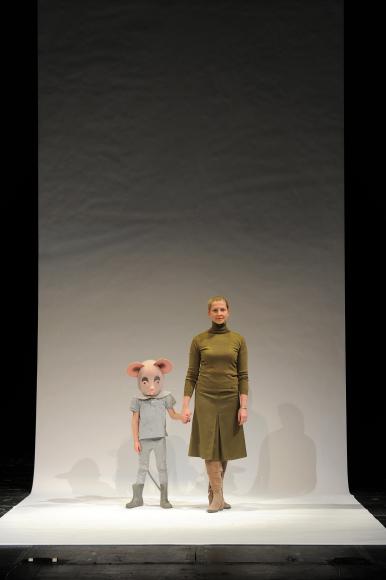

Dampfhart’s comic appearances are links connecting the different pieces. His finest moment: the dance of the “old, sick, widowed elephant” from The Magic Flute. Other connecting elements are recurrent allusions to Bernhard’s last play, which Thomas Langhoff staged at the Burg in 2002. Every portrait tells us something about both the individual and the institution to which they are all attached – inseparably, it seems, whether the subject portrayed is a singing theatre fireman, tourist guide for Japanese visitors, mouse in The Wizard of Oz, or (like Mavie Hörbiger) scion of a family theatrical dynasty. Or a goddess-like apparition such as Christiane von Poelnitz, a diva who emerges from the mists in a white evening dress, shimmering red hair tumbling down her bare back, unable to suppress her laughter when text messages she exchanged with Laub flash up behind her: No way she can make the rehearsal, she plans to have some soup and spend time with her children, or Yes she plans to rehearse, but with a director whose name isn’t Laub. Want to bet that’s exactly how it is for any director putting on a first production at the Burgtheater, Vienna? That newcomers don’t get hold of the actors they had been dreaming of, naturally; that everyone waxes lyrical about legendary productions, of course, about achievements impossible to match. Or that a prior engagement prevents somebody of Maria Happel’s stature from appearing in the flesh at the Laub premiere. She graces the screen instead, declaring she would never part with the secret of her craft, well really, the question alone! It is a matter purely between herself and her audience.

Laub is a past-master in outlandishly dissecting such clichés of the theatre. Who would have thought a Nigerian wrestler has been on the Burg’s books as an extra for the past eight years, a man who sinks his teeth into his opponents’ belts then picks them up and shakes them like a dog would a rabbit? Who can suppress a smile when Elisabeth Aref, soubrette, enters with her tiny pedigree pooch, crosses the stage in her patent leather ankle-boots, quite the diplomat’s widow, and seeks assistance from the prompter – as if unable to memorize the text of her own life? Equally comic the moment when actor André Meyer summons up, by virtue of his powerful description, the full size of the Burgtheater stage presently reduced by means of curtains, and makes it the setting of an imaginary action movie in which he plays a leading role of which he truly dreams.

The most touching scene in a programme that so amusingly lists everything theatre can do – make people smaller or bigger, make them die and come back to life, show dramatic visions of day and night, heaven and hell – belongs to Claudia Durstberger, a singer and bit player. As a baby, she tells us, her survival was touch and go, and even as an adult she retained a longing for death. But, she says quizzically, she got over it eventually, surely everybody can see that? Such a feat can be pulled off by nobody but Michael Laub, pure of heart, takes a cool directorial approach to the employees of a theatre famously rife with intrigues, and strings together what he finds to produce grand comedy. To be alive means to take a bruising, but theatre, ideally, heals all wounds.

Werner Thuswaldner, Salzburger Nachrichten, 27 March 2011

Tragi-Comic Portraits

Burgtheater. Michael Laub places the limelight on 18 of the theatre’s 600 employees, mixing professional actors with authentic amateurs.

Was Saturday’s performance a coded message from the management to the Burgtheater’s principal actors? Was it a subtle way of saying: We can stage a (low-cost) production without you lot, and the audience will lap it up? Look, this theatre has so many gifted employees who can do your job: the fireman able to sing “Walzer der Liebe”, for instance, the theatre guide who speaks perfect Japanese, or the canteen boss who makes an even more convincing Viennese crook than Nicholas Ofczarek.

“Burgporträts” gives each individual about five minutes to talk about themselves. And guess what: everyone has a story that gets you emotionally involved. All of them, it soon emerges, are totally addicted to the theatre.

What’s the story behind Heinzi from the canteen’s strikingly crooked nose? Motorbiking through Vienna as a young man, he was so busy ogling the prostitutes by the roadside that he ended up flying through a car windscreen. An inferno of projected flames leaps up behind the theatre fireman who is fervently rendering “The Waltz of Love”. Frau Höflinger, the ticket-lady, reckoned one year at the Burgtheater would be enough. She has meanwhile clocked up more than 1,400 shifts, and polished off approximately the same number of cheese toasties in Heinzi’s canteen.

And then the bit players! Without their services the Burg could close its doors. Andreas Dampfhart, now retired but with a varied career behind him, shows how he played a man engaged in silent but animated conversation during Thomas Bernhard’s “Elisabeth II.” He also revives his depiction of a mournful elephant-widower in “The Magic Flute”.

The most solid impression is made by Lion A. Kenechukwu from Nigeria, the European wrestling champion. With a bite of steel enabling him to lift opponents up by their belts, he has portrayed bodyguards in several Burg productions. All he needs to do is look dangerous and ripple his pecs.

Karl Heindl fell in love with a Japanese tourist who came to one of his guided Burgtheater tours. After the couple married he lived in Tokyo for a number of years. The marriage failed, but when he returned home history repeated itself. His second marriage to a Japanese woman seems to be more lasting. His Japanese sounds perfect in the spiel he delivers to a group of young tourists, but the names are about all we can make out: Franz Joseph – Katharina Schratt – Hasenauer (the architect who designed the Burg).

Claudia Durstberger demonstrates how she played a naked, blood-covered corpse for director Martin Kusej. Fortunately the blood was strawberry-flavoured. She also talks about her struggle with cancer; how her return to the stage was also her path back to life.

Small people receive some confirmation of their own worth and importance. That’s the conclusion reached by the mother of a developmentally challenged boy for whom playing a mouse in “Wizard of Oz” was an opportunity to show people what he could do.

That’s what makes Michael Laub’s production so special. Put together with laudable sensitivity, it places the limelight on people who normally receive no attention. The portraits have comic aspects, but equally a deep solemnity.

The attempt to integrate a number of leading actors in the production didn’t quite come off. But why? Professionals at ease with a script and a part to play feel suddenly insecure if asked to put their inner beings on display.

Wolfgang Kralicek, Theater heute, May 2011

Laub’s Passport Photo

Thanks to Michael Laub, the stage of the Burgtheater is suddenly the world’s largest photo-booth. One after the other, eighteen different people take position in front of a white studio backdrop and, for a few seconds in some cases, minutes in others, show themselves from their best sides. However, the reward for their efforts is not an EU-standard mugshot but a remarkable evening of theatre with no direct parallel in the long history of that venerable Viennese institution. Laub, a fifty-eight-year-old pioneer of post-dramatic theatre, came to the Burgtheater to implement a portrait concept that produced successful results in a number of different contexts.

The “Portrait Series” evolved from an idea by Tom Stromberg, who in 2002 invited Laub to portray the Deutsches Schauspielhaus in Hamburg; the result was “Portraits 360 Sek.”, and the one-off turned into a series. In Berlin, Laub portrayed dancers; in Istanbul, Turkish women; and in Rotterdam, Rotterdamers. While the principle remains fundamentally the same, the nature of portraiture combined with the varying contexts provides for an ever-wider thematic spectrum with each new instalment.

Insofar as even possible “Burgporträts” refrains from producing theatre. Rarely do individuals seem so mercilessly exposed as they do on this stage, where art is not inserted as a protective barrier between them and the audience. One notes with interest that the canteen landlord who moodily recounts his accidents (motorbike, premiere parties) and his hobbies (home pornos), or the tourist guide who shows parties of Japanese round the theatre and met his wife on one such occasion, cope better with this exposure than do the seasoned professionals. Maria Happel sent in a video recording, Christiane von Poelitz gives the word to the text messages she exchanged during rehearsals (“I’m too tired to occupy myself with different forms of theatre”). Mavie Hörbiger is unwilling to talk about her family history, and Petra Morzé confines herself to two tearful sentences: “My feelings about the Burgtheater are ambiguous. I’m lost in the Burgtheater.” If Michael Laub had chosen to cast actors and actors alone, then these “Burgporträts” would certainly have been hard to take.

Fortunately, the short evening is made up of moments that belong to the bit players and extras, a pool from which Laub cast almost half of his ensemble, with the spectrum ranging from a Nigerian wrestler to a retired soubrette. Several of them appeared in Thomas Langhoff’s production of Thomas Bernhard’s “Elisabeth II.”. Among them is the trained singer Claudia Durstberger, who played a maidservant and now revives a few of her movements only to conclude, drily, “That was Thomas Bernhard.” She then talks with astonishing candour about the physical and mental ailments she has overcome, and also about the worse stint in her career as an extra: her time as a naked, blood-covered corpse in Martin Kušej’s production of Grillparzer’s “King Ottocar’s Fortune and End”. All the same: “The fake blood was agreeably warm and smelt of wild strawberries.”