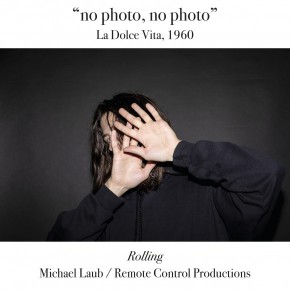

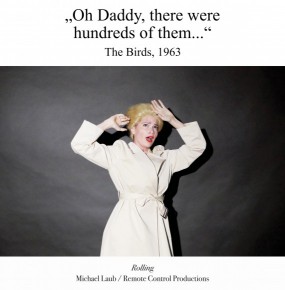

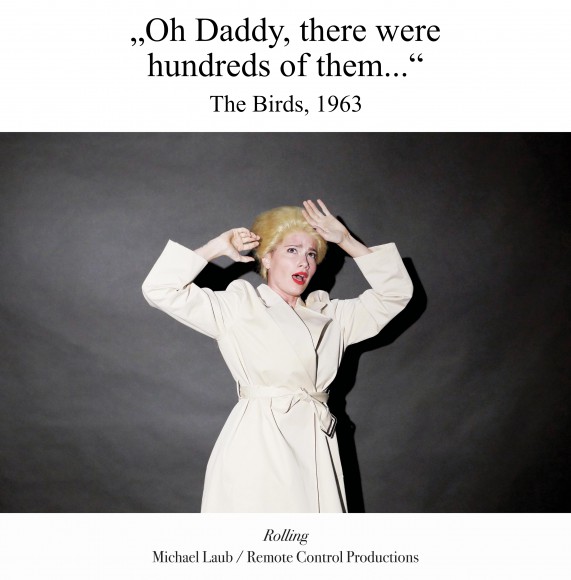

Michael Laub / Remote Control Productions

Rolling (2019)

PHOTOGRAPHY / CREDITS / PRESS

CREDITS

produced by Michael Laub / Remote Control Productions in co-production with HAU Hebbel am Ufer Berlin and ImPulsTanz - Vienna International Dance Festival.

Realised with the financial support of Hauptstadtkulturfonds Berlin.

Conceived and Directed by: Michael Laub

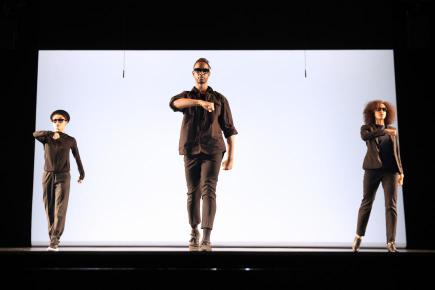

with: Maxwell Cosmo Cramer, Lukas Gander, Tian Gao, Challenge Gumbodete, Melissa Holley, Florian Lenz, Gabrielle Miller, Melissa Anna Schmidt, Isabel Wamig and Greg Zuccolo

Choreography: Michael Laub, Greg Zuccolo and the cast

Video / Technical Director Bodo Gottschalk

Light: Nigel Edwards

Sound Design: Michael Laub

Sound Technician: Toni Bräutigam, Florian Fischer, Torsten Schwarzbach

Assistant Director: Declan Rooney

Production Assistant / Subtitling: Ayako Toyama

Costumes: Maria Roers, Mareile Krettek and the cast

Dresser/ Tailoring: Fabienne-Michelle Grassl

Make-up: Tilo Nethe

Set Elements: Michael Laub / Jean Baptiste Trystram

Film Research: Michael Laub, Samuel Laub and the company

Music: Mute Speaker, original soundtrack excerpts

Artistic / Production Advisor: Michael Stolhofer

Executive Producer: Coralie Morillon

Production Management: Miriam Schmidtke

Project Consultant: Heike Albrecht

Management Remote Control Productions: Claudine Profitlich

PRESS

Helmut Ploebst, Der Standard, 09.07.2019

IMPULSTANZ

Choreographer Michael Laub: From Punk to the Electric Chair

This weekend the Belgian presents his piece Rolling at Impulstanz. Portait of the 66-year-old and his eclectic mixing

Performance, punk – and sometimes good old choreo: Michael Laub has been cutting through cultural history with particular reference to the ‘post-modern’ for over four decades.

His career goes like a rollercoaster. He’s an anarchist with passions for pop and classic, a film freak and Bollywood fan. The Belgian choreographer Michael Laub definitely qualifies as a man with qualities. Now he’s showing his latest piece, Rolling, at the festival Impulstanz.

He isn’t dead yet, but one piece might have been the end of him, shortly after its premiere in Berlin and subsequent performance at Impulstanz 2017. Laub put blood, sweat and tears into Fassbinder, Faust and the Animists, along with Goethe’s Gretchen, Rainer Werner F.’s Beware of a Holy Whore, from 1971, and the Cambodian version of the Madison dance.

He may have taken this work too personally: ‘So I thought it could be taken for my will, or I might take it as such.’ Then he would have to have died, he jokes. But he has a horror of death, and for this reason alone has produced another performance, Rolling, which can be seen at Impulstanz from Friday.

Lithe, nonchalant, self-mocking

Laub fans can leave off the sedatives. At least in the eyes of a medical amateur the 66-year-old looks eminently alive. His figure is in good shape between lithe and slim. His dreadlocks express a certain nonchalant self-mockery. His face has been marked but not ravaged by his intense life. And his voice is as gruff as it was twenty years ago, when the writer of this text first met him – at the Salzburg Festival, where he was showing his then current work Frankula. Its stage design was by Marina Abramović. In 1999 the Belgian-born choreographer, director and video artist already had a turbulent, twenty-five year artistic career behind him. At the time, a lot of nerds were reading Hans-Thies Lehmann’s book Postdramatic Theatre, in which Michael Laub was also mentioned. It was a period of upheaval which deconstructed dance so thoroughly that said German theatre scholar mistook it for theatre. Today Laub is considered a pioneer of post-dramatic theatre.

What did Fassbinder, Faust and the Animists die of? With its large cast, it was well received by audiences and critics alike. Yes, but ‘ironically’, the choreographer states, ‘while I was making a piece about the disintegration of a theatre group during a film shoot, my own company disintegrated.’ The planned tour had to be cancelled. But ‘because I’m such a film freak’, the urge to continue working with this medium wouldn’t let him go.

Chaotic, orchestrated

The result is Rolling, a tornado of around 200 film quotes that were collected in a chaotic flurry and the orchestrated: ‘It has a lot to do with the pop concept of appropriation.’ Which in turn recalls Michael Laub’s effervescent Total Masala Slammer / Heartbreak No. 5, from 2001, in which he mixed Goethe’s Werther up with Indian kathak dance and celebrated the brazenness with which Bollywood cinema makes use of existing art in its very own trashy way.

You can best get to know Michael Laub through this bringing together of opposites. He interlocks dance, theatre, film and music with an obsessive love of detail. ‘But it’s no mishmash. I work through the media systematically.’ For example, he found the cool Madison for the Fassbinder-Faust performance in Jean-Luc Godard’s film Bande à part (1964). For Laub, the Madison, kathak and the classical Cambodian apsara dance are linked in ‘their subtlety and relevance to everyday life’. The elegance of the aspara dance is timeless, he feels, and ‘I have this fascination for certain classical artforms and for trash – Ingmar Bergman and Russ Meyer!’

It was punk – ‘a great liberation – that turned him on to art. His first formation, which brought about neither dance nor theatre but performance, was the collective Maniac Productions, which came together in Stockholm in 1975. ‘I wanted to bring in the spirit of punk, this sound, this trash, this low tech.’ He was obsessional from early on, he laughs. ‘I recently saw a baby photo of me. I was only a few days old, and I was already scowling in disbelief.’

Cut-up technique

He was also influenced by the New York Living Theatre, at least by its collective consciousness. And pop art: ‘When I speak of pop art, I mean Andy Warhol. And his picture of the electric chair. It doesn’t moralise or preach.’ He founded his second company in 1981: Remote Control. The name refers to the emergence of cable TV at the time: ‘I was already interested in William S. Burroughs and the cut-up technique. Now you could change to a different channel, which created a different narrative. I wanted to transfer this concept to the stage.’

He never wanted to make films himself, being too much of a live person. More likely to have become a musician. The rhythm of Miles Davies also had a big influence on his work. A rhythm that even pervades his work when it’s quite realistic, as in his video-portrait series. One of these was seen in 2011 at the Burgtheater, another one later at Impulstanz.

All his works let you feel the anarchist in him. Michael Laub’s career has been like a wild rollercoaster ride. Ultimately he’s always been lucky, he says, with dedicated partners and supporters.

Wiebke Hüster, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 15.06.2019

Unconditional Devotion

The power of celluloid, the power of the stage: the premiere of Michael Laub’s Rolling in Berlin – audacious dance theatre that absolutely had to be invented

Theatre is about the power of the one over the others. The power of origin, the power of politics, of money, the power of those who love less fiercely than they are loved, or don’t love at all. The power of charisma, the power of those whose beauty moves us and breaks down our defences, the power of those who are sexy and use it. It’s about the power of the directors over the actors and the actresses over the directors.

But where is the audience in this structure of mutual dependency? Making the viewers feel that for two hours things happen on the stage that not only interrupt life but also elevate, explain and reflect it, that shock, seduce, paralyse, incite and block more concisely, with more logical consistency and at a faster pace – there’s an irresistible allure for directors here, something they’re willing to strive for. To create these magic events they go to great lengths, put themselves under pressure, compel the unconditional devotion to their intentions in those around them, and in their wider circles awaken expectations they tremble to surpass.

The Belgian director and choreographer Michael Laub, born in 1953, has taken this upon himself since he began working in Stockholm in the mid-1970s. From 1981 his ensemble Remote Control caused a great international stir with its unusual theatre. Blackouts separate many of Laub’s scenes from one another like cinematic cuts. Lights up, lights down, sound on, sound off. The theatre is a place where you can control the elements and actors like a remote control, and you think, as Laub laughingly said in conversation, ‘If only you could in reality too!’

Before anyone gets annoyed, he doesn’t mean it seriously. But his theatre does. Few people know how to play with the power of celluloid and the magic of the stage like he can. His productions actually want to have the effect of films: superficially polished, disturbing below the surface, above all perfectly paced. Laub’s new two-hour-long show, Rolling, in which there is dance like in a musical, acting like in the Burgtheater and singing like in the Met, is no exception, and so the audience have the good fortune of being able to fall head over heels in love with each of the ten remarkable performers for the duration of the evening at no danger to themselves. In Greg Zuccolo, for example, who as the cop from Bad Lieutenant leans into an imaginary car window to spell out to the gum-chewing beauties what sexual services are expected in place of a fine. Greg Zuccolo looks as if he’s stepped out of a Robert Atlman film, but in the excerpts from Swan Lake he dances as if until just last week he’d been under contract at the Bolshoi. Then there’s Melissa Holley, who was dancing the title role in Snow White in Hamburg when she auditioned for Laub. She plays Bette Davies, and says she’ll wait for us to die, and yes, it freezes the blood in our veins. She also sings like Marilyn Monroe in Some Like it Hot, and she’s the title nymphet in the film of Nabokov’s Lolita, and it doesn’t stop there …

What does this all mean, this big acting revue of Michael Laub’s cinema memories? It’s anything other than private, this re-enacted, invoked archive of cut and thrust, lying and deception. These two hundred films rattle about in the cultural memory, from which they are here so charmingly and wittily quoted that you don’t stop laughing for two hours. We’ve all stored Hitchcock’s The Birds in such a way that when Maxwell Cosmo Cramer reads the film titles out from a funny long list on his phone, and then in a signal gesture protects his head with his arms, we break out in laughter. But why?

Laub’s pieces always give the impression of truly audacious dance theatre that doesn’t exist anywhere else but that absolutely had to be invented, so dark and true it is. They perform a lexicon of our cultural-historical expressive achievements. The task given to the actors: express yourselves, singing, dancing, speaking, choking, crawling away with the last of your strength, so that everyone down to the last dullard has to love you, even though you’re pudgy, your face is showing the worse for wear, your legs are too short or your breasts too small. As if that matters, says Michael Laub’s theatre; and it says ‘Roll up, if you want to study the central concept of music, visual art, literature, film and the disciples of this cult. If you want to understand what that is – cool.’

He recently recalled his favourite director, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, in a piece portraying the man’s unforgettable private and artistic sides, his cruelty, his repelling and attractive qualities. Fassbinder was exactly that, a walking promise or his own undoing. But in Laub’s new piece everything’s different. This time he doesn’t just tell us about on-set promiscuity or Bollywood or Hans Christian Andersen, but about the difference between theatre and film, between life and what’s larger than life, its celluloid version.

For the first time Laub turns the process around. In Rolling he no longer wants his theatre to look like film, but transforms the quoted films into theatre, instantly rediscovering them. Laub isn’t concerned with moral judgements, but with how film is grist to the mill of memory and how it shapes our lives.

Musicals make things lighter. Horror makes us go round dark corners in trepidation. We know how love, hate, defeat or victory will feel from hours on red upholstery. Laub, who spent countless afternoons in an old cinema in Brussels during his school days, says that everyone in his generation took up smoking when they saw Jean-Paul Belmondo light up for the first time. And he confesses to travelling to India not in search of God but to study Bollywood. Our preferences? All film.

The choreographer in Laub only really discovered how seriously film took dancing while viewing and discussing his film history. Hypnotic, ritual-like dances create a pull on stage that synchronised movement once did on screen. The piece spins back and forth between trash, commercialism and cinema classics, quote by quote: an aria from Luc Besson’s Diva, ice-cold laughter from Thelma and Louise, the hat, the beach, the Mahler from Death in Venice, hip-swivelling from Boogie Nights.

You’re right, it doesn’t fit together, not in Laub and not in anyone! None of us fit together. Which is why this seamlessly re-enacted recollection is so funny and sophisticated. Because it triggers endless associations, and we can’t keep up with our own thoughts as the marvellous dancer-actors rush through film history. Laub’s completely unacademic approach, decidedly non-objective and non-cinematic, turns this endeavour into a platform for his fantastic ensemble. You feel like watching their slapstick, arias, obscenities and childishness for another two hours, and thank heavens they aren’t hurt when shots bang from the speakers.

‘Rolling’ is of course a film term. It’s in the middle of the three-part order ‘Silence. Rolling. Action’. There’s a rumour that a director’s-cut version twice as long will be shown. Yes please!

Janis El-Bira, Nachtkritik, 12.06.2019

Rolling – HAU Berlin – Michel Laub pays minimalist choreographic homage to the gods of the cinema screen. Oh sublime celluloid!

This evening is bracketed by a kiss between teenage boys and a hail of bullets. The kiss is acted, the bullets are on tape. But both come from another work of art, another medium. ‘This is from Gus Van Sant’s Elephant – a film about a teenage mass shooting in America’ an actor says at the beginning and end. Nothing is seen of this ‘mass shooting’, only heard. And all that’s left of Elephant is this tender, second-long kiss on the cheek.

Film becomes theatre

This is what Rolling, the new work by the Belgian choreographic minimalist Michael Laub and his Remote Control Productions, is about: the media transfer from film to theatre and the fission products left in the filters. We see hundreds of film clips during this peice, but all of them theatricalised. The screen hanging promisingly in the background almost always remains empty. Only surtitles occasionally tell us what we’re seeing. Laub and his ensemble feel out the essentials and untranslatability of film.

Maxwell Cosmo Cramer leads off the vignettes in a long opening monologue. As Leonardo DiCaprio in Romeo and Juliet he boyishly brushes his hair behind his ears; he snaps his left arm like a rubber band in front of his body to indicate the dance scene in Godard’s Bande à part, looks at his phone as Kristen Stewart in Personal Shopper, and stands around with a speer as a Roman soldier in Ben Hur. Later he is joined by his ensemble colleagues. More people, more films, but now sometimes doubly and triply superimposed.

A divine spark even in Sleepless in Seattle

In the best moments of Rolling it almost seems as if the films had willingly reduced themselves to their most recognisable elements. As if even in Sleepless in Seattle there were a divine spark that would define this one film for all time. When it’s captured by the ensemble in these numerous micro-scenes, the entire visual landscape of the respective film seems to light up in the mind’s eye for a short moment. So Melissa Holley drags forth an ice-cold ‘I hope you die!’ from the depths of her throat, and we see Bette Davis in Little Foxes. The dancer Challenge Gumbodete stands at the front of the stage, the screen behind him enveloped in canary-yellow light, and we’re immediately in Fassbinder’s Querelle. An invisible hand seems to be at work on the structure of understanding itself, and tiny little things help us to understand.

Admittedly, not everything is on this level. A few more extended scenes in the second half are too keen on themselves in their microscopically fine mimicry of the stars. At times the ensemble choreographies ravel out and make the evening about twenty minutes too long. But Rolling is fascinating as a study in theatrical appropriation art, even when the ensemble tackle longer film scenes as if they were auditioning. Because film and theatre don’t blend here but encounter one another as essentially different.

At any rate the performers in Rolling look at film as they might see ancient statues: perfect, beautiful, finished and dead. Only in re-enactment does the search for its construction principle begin, do we discern the trace of stones. And because something is always left behind, because some arms and legs can’t swing with such elasticity as Hannah Schygulla’s in Rio das Mortes, the inquiring acting in Rolling is also a homage to the screen gods by theatre people. And we know that down here things are much funnier.

Helmut Ploebst, Der Standard, 14.7.2019

[…]

Change of scene: a young woman traumatised by the brutalities of Mao’s ‘cultural revolution’ and a later war dances into the open in the Chinese film Youth, from 2017. Away from the murdering men, alone beneath the mild moon. Only in this short scene are projected film and live dance on stage – here that of the Akademietheater – in sync. The live dancer is Tian Gao, her choreographer Michael Laub. With Rolling the 66-year-old Belgian has probably created one of his best pieces.

It is naturally possible to ask here whether Tian Gao isn’t a kind of ‘showcase dancer’ for her choreographer. Or does the gender discourse simply not strike home here? Not really, for Rolling deals with film history: with wit and verve, clever selection and wild but well calculated dramaturgy, countless film quotes follow one another, and read together they tell a story. The background to this narrative is film history, which firstly includes the fact that in the first half of the twentieth century, as soon as the film industry began to make a profit, that women were successively forced out of the US film business. And secondly that no other medium has influenced the image of women more massively than film.

And this reminds us that meanwhile several generations have generally been influenced by films, TV series and videos. Michael Laub grabs his audience by its memory. With gestures, hints, poses, a few words, recorded sounds and projected film titles, the dancers and actors build a human memory machine on stage. The beginning and end of this poetic marvel are allusions to a mass murder.

The furious start is made by a single performer reading out film titles from his phone and making very short moments from The Birds, Chunking Express or Ben Hur flare up. The rest of the crew only come on stage after about number forty.

What then unfolds so gloriously shows the richness of film culture. But it also shows how much this abundance manipulates our collective memory.

Martin Pesl, Wiener Zeitung, 13.07.2019

Live Archive of the Cinema: Michael Laub with Rolling at ImPulsTanz

In Rolling the Belgian choreographer pays tribute to 200 films

Is it really going to go on like this for two hours? one asks oneself with a chuckle after the first half an hour of Rolling, the new piece by the Belgian theatre-maker Michael Laub. The principle is always the same: with the declaration ‘This is from …’ one of the ten dancers names a title from the wide-ranging history of the cinema and acts a short moment from it. This could be one of Bette Davis’s famous lines from The Little Foxes (1941) or simply how Leonardo DiCaprio brushes his hair off his face in Romeo and Juliet (1996).

Most of these mini-clips are delivered by Maxwell Cosmo Cramer, who stood out two years ago in Laub’s playful Fassbinder, Faust and the Animists. His love of meticulous imitation appears to be limited, though he can only keep the umpteen films in order with the help of his phone. But his languid quality has something comic about it from the very first, like someone who has to play-act during a board game: is it going to go on like this for two hours?

Remote Control Productions

Michael Laub co-invented post-dramatice theatre in the 1980s with his label Remote Control Productions. His performances always exhibit and question the performance itself. What is authentic, what is pose? In 2011 Laub staged Burg Portraits of staff at the Burgtheater; now he ‘portrays’ a huge number of films in a quick run-through. Why these particular 200 and more remains unclear. But the longer the evening continues, the more varied the immersion becomes. Dance films like A Chorus Line, Footloose or various others, including the ballet Swan Lake, are strongly represented – here the brilliantly choreographed ensemble reminds us we’re at ImPulsTanz.

Some of the performers tend more strongly to enter the foreground, for example the Anglo-German Melissa Holley or the American Greg Zuccolo. Others are more there to fill out the larger group choreographies, which can happen at any time and may last a while or be abruptly interrupted. These performers include the Chinese Tain Gao, who is nevertheless given her big moment. Sliding into the ultimate meta-vortex, she copies a figure from a Chinese film who suffers from amnesia but then remembers who she is from a piece of music and dances to it obliviously.

Imitation machine

When some clips suddenly start to repeat themselves, and to communicate with one another in a certain abstract way, the imitation machine in Rolling has already concentrated itself into an autonomous work of art. Manically or meditatively, this maverick live archive works away at translating all the films we’ve seen or haven’t seen – or rather the vague memory of them – into a language of movement. And then you realise that this evening could go on forever.

Thomas Kramar, Die Presse, 13.7.2019

[…]

Easy-going in comparison, but magical, the festival’s third premiere, Rolling, an admiring homage by the Belgian choreographer Michael Laub to another artform, the one that dominated the last century of our culture: film. Ten dancers, five women and five men, all obviously movie maniacs and quite wonderful, go in and out of roles, re-enacting more or less legendary film scenes, some very short, such as Conan the Barbarian’s hair blowing in the wind or a smile from Thelma & Louise, some longer, such as the death of Gustav von Aschenbach on the Lido, precipitated by a wave from Tadzio, this time even with a commercial break, and it too works in this not only rhythmically perfect montage. Which can of course never end, except perhaps with the Kinks’ ‘Celluloid Heroes’, which Laub unfortunately didn’t choose (consistently, because inexplicably it has never been used in a film). Instead he took ‘Dreams Are My Reality’, but that’s the only thing you can criticise about Rolling.

Edith Wolf Perez, tanz.at, 13.07.2019

Rolling: Talismans of the Collective Memory

[…]

When Michael Laub stages fragments of film, he can rely on the collective memory of the audience. The clips unwind within seconds, from silent classics to contemporary movies.

While two years ago the Belgian theatre director and choreographer looked at Fassbinder’s film Beware of a Holy Whore, from which some scenes appear in Rolling, the current collage from around 200 films reveals the 66-year-old’s infallible theatrical instinct.

For 120 minutes we are fascinated by a theatre piece pieced together from diverse mini-fragments into an unexpected whole. No one in the audience will know the entire palette of quotations in the original, but it’s the timing that does it. We don’t have time to think about the film being quoted (the sources are either announced or appear on the screen in the background).

The ‘glue’ is provided by dance numbers, whether from musicals like Hairspray, A Chorus Line and Footloose or from Swan Lake, Marie Antoinette or Barry Lindon.

The ten performers, all of them dancers, singers and actors in one, are magnificent, and are able to realise this difficult endeavour with precision while also displaying their very individual personalities. They sustain the piece. Other theatrical ingredients – changes of costume, music and sound effects – are used sparely and specifically. The only re-staged scene comes from Visconti’s Death in Venice, when Aschenbach dies against the grand background of the Adriatic with a misty-eyed view of Tadzio (live on stage). Simply captivating!

Peter Jarolin, Kurier, 15.07.2019

Dar¬ling, I’m in My Great Mental Cinema

Michael Laub and Remote Control Productions are a delight with Rolling at the festival ImPulsTanz

Dancing images from the film-historical canon: Laub’s Rolling

The Belgian choreographer Michael Laub is well-known as a maniac, an obsessive, a first-class cineaste. He loves films, great cinema, which he consistently relates to various dances with a brilliant montage technique.

This was the case in Fassbinder, Faust and the Animists (2017) at ImPulsTanz), in which Laub enjoyable examined Fassbinder’s Beware of a Holy Whore. In his new work, he goes at step further with a marvellous ensemble of ten.

Lassie must suffer

No longer is just one film the subject mater (as a guest performance at the Adademietheater). No, Laub takes on around 200 film classics and links them to the ruthless struggle for roles, fame and wealth, juxtaposing the sunny side of Hollywood with an American high-school massacre and China’s aspiration to world cinematic power. It isn’t far (and not only in film terms) from the dead dog Lassie to real acts of violence.

Sissi must dance

Performer Maxwell Cosmo Cramer begins every sentence with ‘This is …’, and follows it with famous quotations from the European and American cinematic canon.

Marlene Dietrich and Bette Davis, Robert de Niro and Sylvester Stallone, Marilyn Monroe and Tippi Hedren, Leonardo DiCaprio and Jack Nicholson, or Romy Schneider in Mädchen in Uniform or to waltz music as Sissi – Laub quotes, imitates, ironises, parodies and reflects. Visconti’s Death in Venice becomes as much of a tableau as Fellini’s [sic.] Bicycle Thieves or scenes from Good Fellas. And the postman naturally rings twice for Laub.

There must be humour

Dance and acting are recurrently montaged, and scene follows scene before Laub and his multilingual expressive performers leave the celluloid metalevel and turn the spotlight onto reality. All this occurs with playfully dancing lightness, in hard cuts and much humour. For Laub exaggerates and builds up dramatic falls, only to take pleasure in interrupting them.

The onstage screen remains blank for the most part, and is only used occasionally. For example in Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor, when suddenly the issue of uniformity and enforced political conformity in Mao’s China comes up. In this scene Laub touches on a painful reality.

After two hours without an interval, the happy end is also foiled. After the very last acted film scene we hear shots. ‘This is …’ says Maxwell Cosmo Cramer again. But now it’s not about magical images or stylised violence. The shots of a high-school massacre are the final echoing mental images. Superb!