Michael Laub / Remote Control Productions

Portrait Series Rotterdam (2010)

PHOTOGRAPHY / CREDITS / PRESS

CREDITS

conceived and directed by Michael Laub

dramaturgy and video Astrid Endruweit

light design Nigel Edwards

technical director Jochen Massar

assistant director Ebru Karaca

assistant production Stefanie Vermeiren

sound Gerard Wilegers

performers Fabian Holle, Michelle Bauer, McGregor Spalburg, Jeroen Rienks, Ariette Furtado, Sandro Lima, Gonny Gaakeer, Jan de Bruin, Afke Weltevrede, Denvis Grotenhuis, Luis Rios Zertuche, Ralph van den Brand. On video: Fouad Mourigh, Carole Hietbrink, Joany Muskiet, Annemarie Hagenaars

stagehands Wouter Schreuder, Sander Verbeek

intern Ise Donckers

management Michael Laub/Remote Control Productions Claudine Profitlich

produced by Productiehuis Rotterdam (Rotterdamse Schouwburg) i.s.m. L/V producties

with special thanks to Samuel C. Laub

PRESS

Marietta Piekenbrock, Head of Artistic Programming City of Arts RUHR 2010, from: Formen kuenstlerischer Zusammenarbeit. Sophiensaele 2007-2010, published by Heike Albrecht and Matthias Dell. Berlin 2011.

Death, Dance & Diversity

About Michael Laub and Remote Control Productions

“Hello, I’m Robert” – “I’m Asli, who happened to be born in Istanbul” – “My name is Günce” – “I’m Seher Sentürk” – “Hello, I’m Greg”. They use their real names on the stage, and altogether make little effort to be anybody other than the person they consider themselves to be. All of them were chosen by Belgian director-choreographer for the casts of his new portrait series in the cities of Istanbul and Rotterdam, as well as in “Death, Dance & Some Talk”, a tragi-comic evening about life on the chorus lines.

The portrait format was inspired by Tom Stromberg during his term as intendant of Schauspielhaus Hamburg. Fascinated by the portrait-like character of earlier solo performances given by members of Remote Control, Stromberg commissioned Laub to produce a series of six-minute cameos giving actors and staff from the theatre a chance to speak in the first person.

In contrast to works such as August Sander’s epochal visual atlas “People of the Twentieth Century”, the series of portraits Laub groups together under the respective titles Berlin, Rotterdam and Istanbul make no claim to represent any one sector of the population, any social, professional or urban class. “To take, like Sander, specimen after specimen, seeking an ideally complete inventory, pre-supposes that society can be envisaged as a comprehensible totality,” wrote Susan Sontag. Michael Laub’s work has little in common with the encyclopaedic vision of society as a recordable entity able to be broken down into typologies and archetypes.

Laub’s passion is the flaw in the system: the irritating detail, the disturbing memory, the imperfect body, the unique experience, the innocence that is unspoiled, the distress that is extreme. The short stories delivered by his performers oscillate between normal and glamorous realities until a blurring sets in of the border between art and “life”, between professional and amateur, between intentional and accidental. One might also say: they celebrate miscellaneous versions of the authentic.

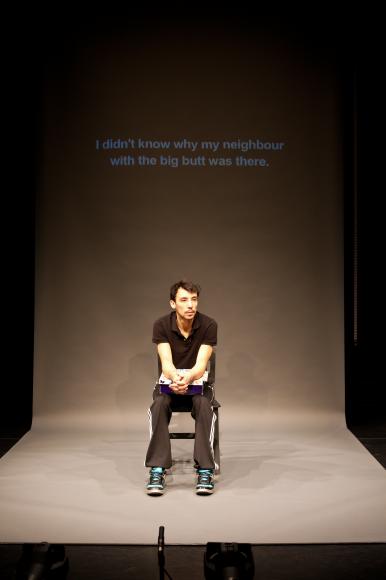

It is an effect reminiscent of Surrealism, except that Michael Laub invariably directs our attention to the artificiality, the made-ness, of his pieces. We see a photographer’s studio on the otherwise empty set. Stage technicians appear between the individual appearances, tug at wires, push chairs about, adjust the lighting. These are clear signals: the space of the stage is not an enclave of power but an open studio that creates a proximity to the audience, a proximity within which fluid self-portraits intersect with representations of other people.

The classical studio portrait is a kind of ceremony in which, to put it simply, the subject becomes the object. Who has not seen a photograph of themselves and experienced the harsh moment of truth: That’s not me! That’s not the person I consider myself to be.

What happens in Michael Laub’s pieces is different: one experience superimposes itself over another, and both of them lay claim to their own reality: that of the subject being considered, and that of the subject experiencing and proposing itself at the same time. It is a matter of compulsory versus voluntary self-revelation in a society in which the art of representation determines private and public life in equal measure. The director’s role is concentrated on accentuating this given situation, of finding a rhythm and arrangement for this situation, without undertaking a valuation or establishing a hierarchy. The subtle presence of the director provides the formal and emotional framework for collective, non-closed authorship.

The portrait subjects decide themselves which pose they want to try out, which aspect of their past they want to present, and on the manner of their appearance and disappearance. Greg, Asli, Robert, Wilma, Fabian, Ariette or Jeroen – they all establish a presence that allows anything omitted or not articulated to undergo explosive multiplication within the viewer’s imagination. Every gesture, every sentence, of their sketch-like outlines defends the free-floating core of their existence, the vulnerable right to individuality.

The live-shots delivered by Michael Laub and his cast of performers amount to a theatrical visual atlas about people in the 21th century and the difficulty of existing in, and before, the eyes of the others. And that is what makes these portraits so magnetically powerful, so politically topical.

Portraits Rotterdam, a

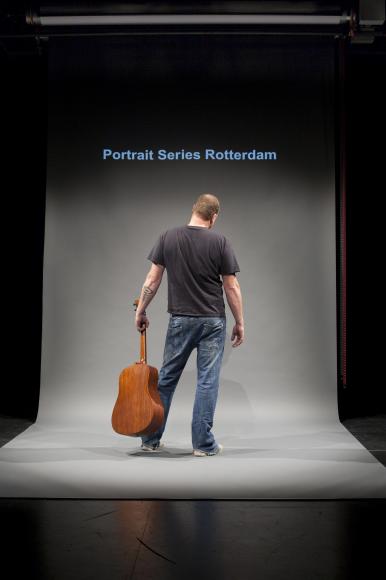

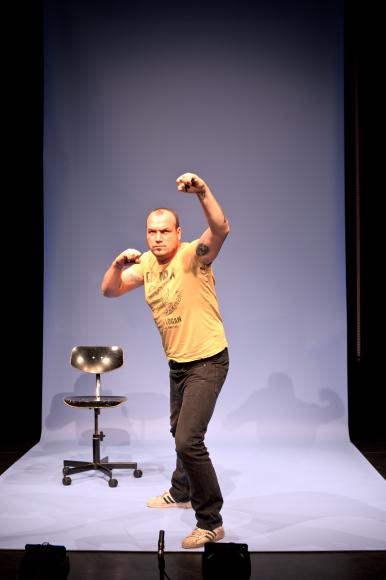

text by Jost Ramaer, 2011

Denvis Grotenhuis is a big guy. “People from Holland are big, there is not a lot we can do about that.” The tattoos on his arms are big, too. This particular combination –a big guy with big tattoos – often seems to intimidate people. The other day, when he was travelling on a tram in his native Rotterdam, a mother looked at him rather apprehensively and pulled her little daughter close to her. Denvis just doesn’t get this attitude. Actually, he feels rather insulted by it. “I have feelings too, you know.” He sings a song he composed himself, playing his guitar. He sounds and acts like he is singing the blues about the tough life. In reality, the song is about his dog, who recently died on him. “It broke my heart.”

Denvis performs in Portraits Rotterdam, the fifth instalment of the Portraits-series by Michael Laub, a French-Belgian veteran of the European avantgarde theatre. All Portraits are made according to the same formula. Laub links up with a theatre or a theatre ensemble in a European city, who will select a pool of local people to audition for him. During these auditions he asks them to tell a story from their personal lives, with the help of any media they want to bring. From this group he selects about fifteen tales and tellers – sometimes he’s hooked by the story, sometimes by the performer, often by both. Then he hones every individual story and performance to his satisfaction. Finally, he arranges them into a fluent show. During the whole process Laub works closely with a small band of confidants: dramaturgist Astrid Endruweit, designer and producer Ebru Karaca, light designer Nigel Edwards and technical director Jochen Massar.

Laub always starts the auditions with a broad outline in his head of the show he wants to make. Led by the tales of his prospects, he will invariably see his own original idea develop into something completely different. This is exactly as he wants it. Although Laub trained as a professional actor and has worked on stage all his life, he considers the theatre “a trashy art form”, stuck in its huge legacy of Shakespeare, Schiller and Racine, unable or unwilling to embrace modern media. All his shows aim at “deconstructing” theatre.

Laub is a gentle warrior, brandishing not a shield but a mirror, to the actors as well as the public, to let them discover by themselves their false mannerisms and expectations. He always works with a mix of professionals and talented amateurs he recruits himself, often bumping into them by pure chance. During the making of his shows he constantly and deliberately downplays his own role as a director, as well as the usual attributes of showmanship on stage: stardom, drama, exaltation, egotism. Laub prods and questions the members of his ad hoc ensembles to come up with their own stories and ideas, to guide him instead of being told what to do.

All this he does on the stage he professes to loath, and the contradiction doesn’t stop there. When Laub finally decides on the format for a new show, he becomes a stickler for perfection, arranging even the minutest details himself, like a true director. Still, what his audience gets to see is always a testament to his concept of deconstruction: an implicit, almost accidental story, totally devoid of drama – but a story nonetheless. He loves to fudge the issue. “Ask people what a portrait is in painting or in literature, and they will instantly give the answer,” he says. “But a portrait in theatre? Even now I find it difficult to say what that is.”

Whatever they are, Laub’s Portraits offer their public real, visceral, almost documentary experiences. During the prolonged journey from auditions till opening night – he always insists on a minimum of six weeks of preparation – the apparent hotchpotch of small, personal life stories melts into a portrait of a city, of a culture, of a community.

Portraits Rotterdam is no exception. He made it parallel to Portraits Istanbul; the latter opened in garajistanbul on April 28, 2010, Portraits Rotterdam five months later in the local theatre cum arthouse cinema Lantaren/Venster, during Internationale Keuze (International Choice), a yearly selection of avantgarde shows from all over the world by the Rotterdamse Schouwburg, the port’s city theatre. The two offer an interesting comparison.

The Turkish women in Istanbul bristle with the pain and energy of a young, unstable and often cruel society. Their tales are full of torture and hardship; many of them come from broken families, and had to work for money as little girls, to help feed their brothers and sisters. It makes their dreams all the more powerful. They all hope to become actresses one day in Turkey’s vibrant entertainment industry. It is obvious that most of them will never even get close to reaching that goal. But that doesn’t matter. What comes across, is their sheer will to make the most of their lives. When you grow up poor and uneducated, shackled by a culture of female servitude, you better make sure you get the hell out of there. In a country like Turkey, there is still a lot to strive for – especially for women.

The accidental actors in Portraits Rotterdam are just as honest and open and endearing as their Turkish counterparts. The Dutch are not just big, they are like that, too. But their life stories are very different. For the last decade Holland has had its fair share of the usual problems of predominantly white, affluent Western societies: an erosion of the old consensus and an upsurge of new anxieties, in particular about race, religion and immigration. In this respect Rotterdam has fared worse than most bigger cities in the country. The port’s population is poorer, less well educated and knows a higher unemployment rate than most. Apart from that, Rotterdam has housing problems almost unheard of elsewhere in Holland: whole blocks of deserted and dilapidated houses in its poorer neighbourhoods, especially in the south of the city.

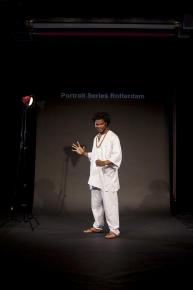

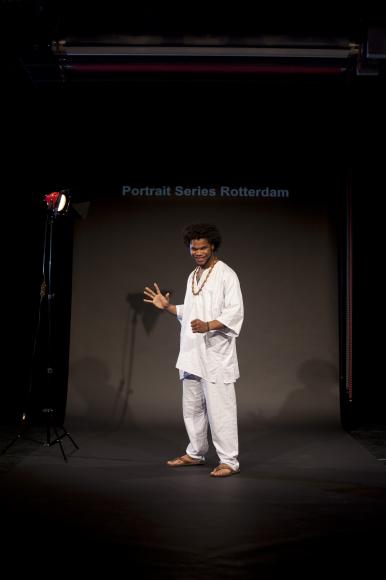

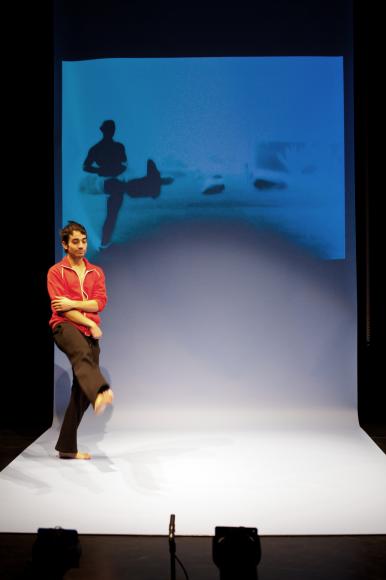

Somewhat surprisingly, these troubles are largely absent from Portraits Rotterdam’s tales, even though quite a few of the players are coloured people from Surinam or the Cape Verdians – a sizable immigrant community in Rotterdam. Joany Muskiet sings her own song, full of praise for Rotterdam, the city she loves. McGregor Spalburg recounts the one moment in his life “when I actually wanted to kill somebody”: a burglary, depriving him and his fellow band members of all the recordings for their first album, because they had forgotten to make back-ups.

Ariette Furtado sings her own song too, with a pained and serious look on her face. “I want to be who I am,” she proclaims at the end, as if she isn’t who she is. In sharp contrast, 30-years old “African-Dutch-Cape Verdian” Sandro Lima, born and bred in Rotterdam, misses his beloved islands, but he still wakes up with a smile on his face “every fucking day”. Luis Rios Zertuche, a young designer, charms the audience with his tale of how he keeps in touch with his lover in New York: they both leave their computers on Skype day and night, even while they’re asleep. Michelle Bauer tells about her days as a ‘Lolita’-performer in Now&Wow, Rotterdam’s legendary dance club. Once, the Lolita’s had to wear translucent white dresses. One of the girls had her period, and thought “the blood a bad match with the white fabric”. Whereupon the producer of the Lolita-shows airily suggested: “We should paint all your crotches red.”

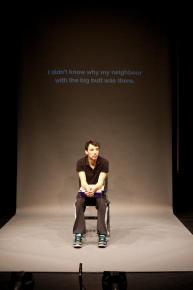

In short, most of the stories are not just personal by nature, but also by subject. They may be sad, serious, funny or a combination of those, but they will rarely show glimpses of the outside world. The two main exceptions are Annemarie Hagenaars and Jeroen Rienks. Annemarie and a friend happened to interview Pim Fortuyn, the right-wing politician who used to live in Rotterdam, for a school project, literally hours before he was murdered on May 6, 2002. Before the interview Annemarie tended to see him as a “bad man”, with bad politics. But during their talk she inevitably grew a little closer to Fortuyn and his ideas. She realised the world “was not so simple”. Afterwards Annemarie and her friend posed with Fortuyn for a picture, her hand resting on the shoulder of his bespoke pinstripe suit. When her friend informed her later that afternoon about his murder, at first Annemarie refused to believe her. “I was disappointed in the world and everyone,” she says, with tears filling her eyes. “How could a man who was wearing a very soft suit … lying there on the parking place with the same suit … ” She never completes the sentence.

Jeroen Rienks, now a 44-year old married father of two, tells a dark tale from his military service in the early eighties. He and his room mates turned increasingly on one of them, Onno van Duivenbode, considered a “whimp” because he kept a picture of his mother on the inside of the door of his personal closet, instead of the usual centrefold from Playboy or Penthouse. Their harassment of Onno escalated when they tied him to his bed after returning to their base, drunk from a night out. Hours later, they were woken up by Onno, screaming. He had fallen over, flat on his face, and broken his nose and jaw in the process, as well as three teeth. Onno was carried away to hospital. “We never saw him again.”

Rienks is Laub’s personal favourite in Portraits Rotterdam. He loves it when a seemingly ordinary and decent person bares a darker side of his life and makes the audience feel distinctly uneasy. That is an integral part of Laub’s vision of theatre deconstructed. The fact that Portraits Rotterdam rarely disturbs the comfort of its public may have something to do with its selection process: as in most Portraits-instalments, Laub mainly recruited players with at least some background in the performing arts, professionally or as amateurs. This may have slanted his choice of tellers and tales towards what will work best on stage, instead of the most realistic portrait of Rotterdam and its explosive mix of poor and rich, white and coloured, unemployment and hard work ethics, university and lack of education.

On the other hand, there is no doubt that tales of the dark do not exactly dominate the contemporary collective experience of the Dutch, despite all the disturbing new influences creeping up on us. The likes of Onno van Duivenbode are safer since the Dutch government suspended compulsory military service years ago, in spite of a growing range of military commitments.

As a show, ‘Rotterdam’ is also Michael Laub’s favourite instalment of the series. To start with, it was a virtual sell-out on every of its four evenings. “It was perfect,” Laub says. “I really had the feeling that my show reflected the atmosphere I felt while roaming the streets of that city.” He may well be very right about that. The Turkish women in Portraits Istanbul strive for better lives against impossible odds. In comparison, the Dutch are still very well off, spiritually and materially. Their typical agonies are best illustrated by Denvis Grotenhuis’ dilemma: should he or should he not let a new dog enter his life?