Michael Laub / Remote Control Productions

Portrait Series Istanbul (2010)

PHOTOGRAPHY / CREDITS / PRESS

"Hello. I‘m 37 years old. I was born in a village close to Samsun. My family was in Istanbul. I stayed in Samsun separated from my family I stayed with my grandparents. I went to elementary school in Samsun. In the summer holidays I worked in the village fields. I planted tobacco. I carried the fertilized water to those who were planting tobacco. That water chapped my hands covered them in wounds. After graduating I went back to my family in Istanbul and started to work. My first job was ironing at a textile company. I was 12 years old. Standing all day ironing, my feet hurt but I didn't let the employer know so he would not fire me. After I left that job I stitched tags. During that time my father went to Saudi-Arabia as a construction worker. After my father left I became the man of our household. I looked after my family. During my father’s absence we lived through a hard year. Our home was flooded,someone burned down our coalhole the money I earned wasn't enough for our family. We had trouble getting by. We didn’t have enough to eat. I was skinny back then and lost even more weight when my father returned. I started to work in a big company as a machine operator. Even though I wasn't trained for it, I worked there for one month. I learned by doing it, without letting anybody know. At my next place of employment I met my first love. But we broke up after one and a half years. He was the driver of the company’s shuttle bus. I loved my first love deeply I’ve never forgotten him. The company downsized I lost my job. I got married when I was 20. I have two children. I provide for them by working. The first years of my marriage were full of problems. Now when I go home after work what I enjoy most is to check on facebook and

watch videos. I daydream a lot. I imagine myself as the actresses I see in commercials and films. Even when I feel very down. I can start to dance and sing within ten minutes. I love to daydream. I love to singwhile I’m cooking or washing the dishes. What I wanted to do most was to see a play in a theatre. I never had any opportunity to see theatre. Now I'm the cleaning lady of a theatre. I was unemployed looking for work. A friend told me about a job opportunity and told me to interview for it. During the job interview I was told that I would work in a theatre. I was so happy my dream became true. I took the job immediately. Now I'm the cleaning lady of a theatre. I'm very curious to see what my future holds. I hope for good things to come. Briefly, this is my life". (Filiz Alt)

CREDITS

Concept and Direction Michael Laub

Dramaturgy and Audition Videos Astrid Endruweit

Assistant Director Ebru Karaca

Light Design Nigel Edwards

Sound Ata Güner / Jean-Pierre Urbano

Technical Director Jochen Massar

Video Operator Onur Tetik

Production Management, Subtitles and Display Operation Asli Demir

Istanpoli Project Coordinator Aytunc Demirkaya

Production Assistants Merve Dogan, Burak Apaydin, Ufuk Tan Altunkaya

management Michael Laub/Remote Control Productions Sven Neumann, Claudine Profitlich

Curator Maria Magdalena Schwaegerman

Performers Dilah Demir, Makbule Tüzüner, Seher Åžentürk, Asli Bostanci, Aye Burcu Eren, Filiz Altnta, Günce Miraç Dizman, Ahu Güral, Sevgi Keskin, Berrin Karaba, Sare Cidem TekelioÄu Demir, Yasemin Öztürk, Suzan Elif Kilinç

on video Zeynep Gülçin Yurdabak, Serpil Semra Yurdabek, Perihan Kurtolu, Eda Yildiz

Stage Hands Utku Kara, Tugay Boz

Worldpremiere: garajistanbul, Istanbul 28. April 2010

Produced by garajistanbul with the support of Istanbul 2010 European Capital of Culture Agency

Co-produced by Remote Control Productions, Rotterdamse Schouwburg, Stadsschouwburg Utrecht

PRESS

Wiebke Hüster, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 4 November 2010

Princes Take a Back Seat

Michael Laub discovers the artist inside every woman

“The world,” Belgian choreographer-director Michael Laub tells the Turkish newspaper Hürriyet, “is full of artists or people who think they are artists; but even more people out there are artists without knowing it.” Wherever Laub travels to produce a new instalment in his series of theatre portraits, he

organizes public auditions in order to find new self-portrayers. And whatever kind of cast life comes up with: Laub’s job is to put the individuals on the stage.

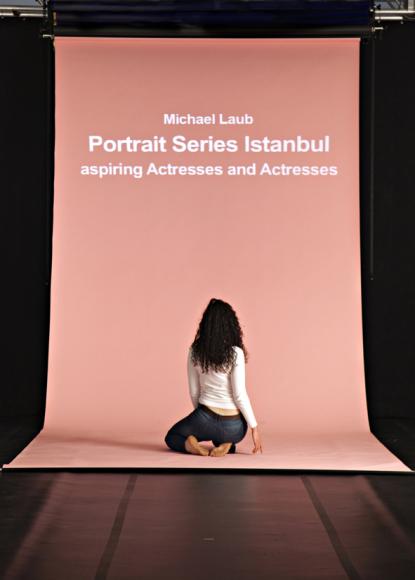

Two hundred candidates turned up for auditions in Istanbul, where “Actresses and Aspirants” came about. The piece now premiered in Germany at PACT Zollverein, Essen. Seventeen women were chosen, and what they recount, dance, sing, or perform to music – in some cases, we only see video footage – is the re-enacted, edited version of what they presented to Laub and his dramaturg, Astrid Endruweit, during the auditions. This adherence to a predefined structure is as simple as it is amusing.

One woman at a time appears in front of background paper rolled out like in a photographic studio, and begins her presentation. Most of them face the audience straight on and are not in costume. Many of them recount who their parents are, where they come from, and their line of work, which in most cases was chosen in compliance with their family’s wishes. They say that they dream of the theatre, or explain why they’re wearing a Peter Pan costume. One woman, a professional actress, just stands there without speaking then exits in her white polyester dress. One woman presents excerpts from the popular TV series in which she plays bit parts, and shows how she inevitably gets the worst of various stormy family dramas. The shy charm and sober matter-of-factness with which Sevgi Keskin demonstrates how she is humiliated, pushed about and beaten is utterly disarming. Apparently, she doesn’t mind always being the scapegoat, and still less does she have any awareness of the lurid nature of the soaps in which she appears. A mother and daughter interviewed only on film express their fear that the male head of the family will be anything but amused by their escapade as Laub performers, and end by saying they will need to ask his permission. Laub never heard from them again.

The ladies of Istanbul take their turn over the duration of ninety minutes. Filiz Altintas, a theatre’s cleaning woman, laughingly presents a belly dance wearing a yellow T-shirt sporting the words “Cleaning Team”. Seher Sentürk explains that she was sent to the auditions by her actress daughters, who said she was the one with a story to tell. This story, and this one only, has nothing to do with the theatre. Sentürk’s tears are real as she delivers an account of the Turkish military coup in 1983, and the subsequent arrest, interrogation and torture of herself and her husband. The courage she displays in reporting on her fate, performance for performance, rouses the warmest applause.

None of the other stories possess the same sense of destiny. None of the women wants to be an actress, or has become one already because real life was so intolerable. They don’t dream of certain leading roles, of famous directors or Hollywood. The interesting thing is – and in this the Turkish women hardly differ from many of their European counterparts – that they seem utterly indifferent to the context. It’s all about the opportunity to take the centre stage, to feel the glare of the spotlights, to put on make-up, get dressed up and say something or another. Is that what these women (none of whom none, by the way, has covered her head) consider to be the ultimate freedom? If so, then it’s an important finding – for directors, at least: they’ve inherited the role traditionally reserved for fairy-tale princes.

Melanie Suchy, Süddeutsche Zeitung, 8 November 2010

Women In Front of the Lenses

Performers stage their own persons in Michael Laub’s Essen performance “Portrait Series Istanbul”

Fifteen women take their bows at the end. The applauding audience sees them together for the first time. They had appeared separately: some bold, others bashful, taking the stage with measured steps. A kind of photographic studio awaited them. A roll of background paper suspended from a bar offered the requisite underground for the personality being laid bare: a vast and voracious lens to which the women were exposed. Of the fifteen women, only two are professional actresses.

And non-professionalism is the subject of Michael Laub’s new piece for the stage, premiered in Istanbul at the end of April. The Belgian calls it “Portrait Series Istanbul” with the subtitle “Actresses and Aspirants”. The German premiere now took place at the “Favoriten 2010” festival in North Rhine-Westphalia, where the non-sensational piece with no desire to be exotic was part of an exchange of projects between the European Cultural Capitals Ruhr.2010 and Istanbul.

The vast stage in Pact Zollverein choreographic centre, Essen, contrasts harshly with the women standing alone on the roll of paper. They animate the sparse environment with their bodies, their movements, their words (and usually wear casual dress). What they say in Turkish or English is rendered in German by overtitles. There is something relentlessly impersonal about the printed sentences. The letters don’t tremble when a woman weeps as she remembers her husband and how the couple was brutally incarcerated in the 1980s, nor do they fade to match the toneless whispering of a university graduate who now works in a call centre.

The titles state every single name, translate every “Merhaba” into “Hello”, specify “Actress” when a lady appears in a white dress and throws open her arms, wordlessly and passionately, or a gaunt woman in net stockings just stands there, staring into the audience-lens as if expecting to be booed off the stage. Attention is what they all want. Many of them talk about their dream of becoming an actress, of the freedom to be “creative” – and perhaps just mean the possibility to be different from the way they are or feel themselves to be.

Michael Laub has presented performances since 1975, and moved on to works for the stage after founding his Remote Control Productions in 1981. He creates pieces that elude conventional theatricality and blend elements of diverse genres such as film, dance, and musical. In 2002, in response to a request by Tom Stromberg, he began working on portraits in a photographic studio setting at the Schauspielhaus Hamburg. Since then he’s repeated the exercise in Rotterdam and Berlin, and devoted a portrait to Marina Abramovic in Rome. The Istanbul version is interspersed with videos in which other women document the audition situation in which they were expected to speak, sing, dance and show photographs.

Afterwards we know no more about Istanbul than we did before. The women, too, remain alien, individuals presented in series, and as such not so very different from their audience. The perfectly sequenced portraits aim neither to dig deep nor to make sweeping statements. They simply honour the women with no attempt to disguise the banality of their descriptions of life, of their efforts to place themselves in scene. As an example of contemporary, unheroic art, this “Portrait Series” is worth seeing; at the same time, however, it leaves behind an unpleasant sensation of emptiness.