Michael Laub / Remote Control Productions

Galaxy Khmer / Portrait Series Battambang

PHOTOGRAPHY / CREDITS / PRESS

Galaxy Khmer (2014)

Concept and Direction Michael Laub

Music The Cambodian Space Project: Srey Channthy (Vocals), Bun Sophea (Bass), Julien Malcolm Poulson (Guitar), Yus Sak (Percussion)

with Phare Productions International: Ly Vanthan (Tro/Percussion), Peou Pitey (Khim), Touch Srey (Roneat)

Dancers Ly Teyva, Khen Vanthurn, Khen Vanthy

Visuals Marc Eberle, Tim Huys

Assistant Director Declan Rooney

Light Thomas Schmidt

Sound Stephan Wöhrmann

Video Assistance Bodo Gottschalk

Production Cambodia Jean-Christophe Sidoit

Production Berlin Bergen Jana Bäskau, Sven Neumann

Tour Management Xavier Gobin, Coralie Morillon, Sven Neumann

Thanks to Astrid Endruweit

Produced by Phare Productions International branch of Phare Performing Social Enterprise

HAU Hebbel am Ufer, Berlin

BIT Teatergarasjen, Bergen

House on Fire with the support of the Cultural programme of the European Union

Michael Laub / Remote Control Productions

Funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and The Norwegian Association for Performing Arts

Portrait Series Battambang

Directed by Michael Laub

with Kiry Chhim, Chanreaksmey Srey, Leout Porn, Khema Chhuon, Veng Mav, Chan Minear Choun, Pon Channiat, Chan Neary Choun, Nara Pan, Vanny Yout, Soknan Nat, Sopheara Chea, Mohamed Saliou Bangoura, Samnang Phat, Yeethien Mao, Sok Kheang Rem, Sophea Houn, Johnny West, Sophea Mao, Bun Reasmey Chea, Reaksmey Yean, Pun Sochea, Chan Sovanna Srey, Sokuntevy Oeur, Samnang Nut, Maly, Srey Mean Bun, Khoun Soun, Leakena Bun, Nicolas C. Grey, Vuthy Touch, Yuri Holi, Chandy Chhuon, Teang Sam, Chanpheaktra I, Srey Leap Nov

Co-Produced by Michael Laub, Phare Performing Social Enterprise Co. Ltd, HAU Hebbel am Ufer

Director of Photography and Editor Ebru Karaca

Production Management Xavier Gobin

Artistic Consultant and Production Assistant Mathieu Ly

Production Assistant Reaksmey Yean

Light Jochen Massar, Yeethien Mao

Sound Mix Jean-Pierre Urbano , Border Arts Studio, Professional Audio Productions

Translators Rithisal Kang, Kunthy Sok, Dilen Hin

Social Worker Dalin Nou

Subtitles Sarin Chhuon

Stage Hands Yeethien Mao, Sok Kheang Rem

Technical Crew Sophea Mao, Yeethien Mao,Sok Kheang Rem

Location Assistants Sovankiri Thuon, Vichheka Van, Sopheak Sam, Kosal Sam

Thanks to Jean-Christophe Sidoit, Mathieu Damperon, The Cambodian Space Project

PRESS

Patrick Wildermann, Der Tagesspiegel, Kultur 16 01 2014

Weep As Loud As You Can

Performance, film and rock-’n’-roll: a Cambodia festival in Hebbel am Ufer.

It was the day of tears. The first woman entered the studio and began, tearfully, to tell her story. “Heart-rending,” says Michael Laub. The second woman arrived one hour later, sobbing her heart out. Later, the third woman arrived. “There wasn’t much difference between their stories,” the artist reports. In some cases the wife-beating husband was an alcoholic to boot.

Now, it’s hardly surprising to encounter appalling fates in a country so impoverished as Cambodia. All the same, it’s astonishing to see a scene in Portrait Series Battambang in which five female protagonists all weep at the same time. An orchestrated cacophony of wails, peculiarly comical and alienating.

“The women themselves began to play with the situation,” the director assures me when I talk to him in Berlin. They asked for repeats, directed each other’s floods of tears: Hey, you can do better than that!

Something Laub has asserted in relation to more than one of his previous productions takes on a new dimension against the present backdrop: “I wasn’t looking for trauma; it found me.” Together with HAU boss Annemie Vanackere, the Belgian-based artist-choreographer is responsible for the project “Staging Cambodia”, which has the subheading “Video, Memory & Rock-’n’-Roll”.

“My fascination with Cambodia comes, like most things in my life, from fiction,” Laub readily admits. As a youngster he overdosed on Apocalypse Now, in the late 1990s he travelled to Phnom Penh, equipped with a travel guide that summed up the “sick nightlife” of that era in one deft heading: “Into the Dark Heart of Girls, Guns and Ganja”. No project resulted from his trip back then, and nor did he have a project in mind when he travelled to Battambang.

By a roundabout route Laub had come into contact with the Phare Ponleu Selpak Association. The NGO is engaged in reviving the kind of Cambodian cultural life that Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge tried to destroy in the 1970s. The organization has its own school for circus artistes, and teaches classes in the visual arts, photography, and music. Laub reckoned he might be able to stage a workshop “for all those youngsters with bleached blond hair”. Instead, the project placed in front of his camera traumatized individuals from the neighbourhood. “I’m no social worker,” Laub stresses. And he doesn’t get off on other people’s misery either. But one thing he is: a remarkably good observer of people.

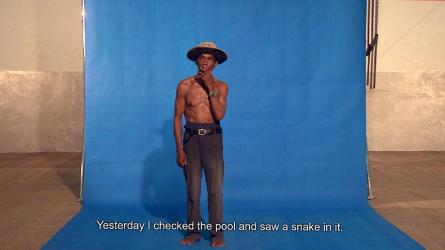

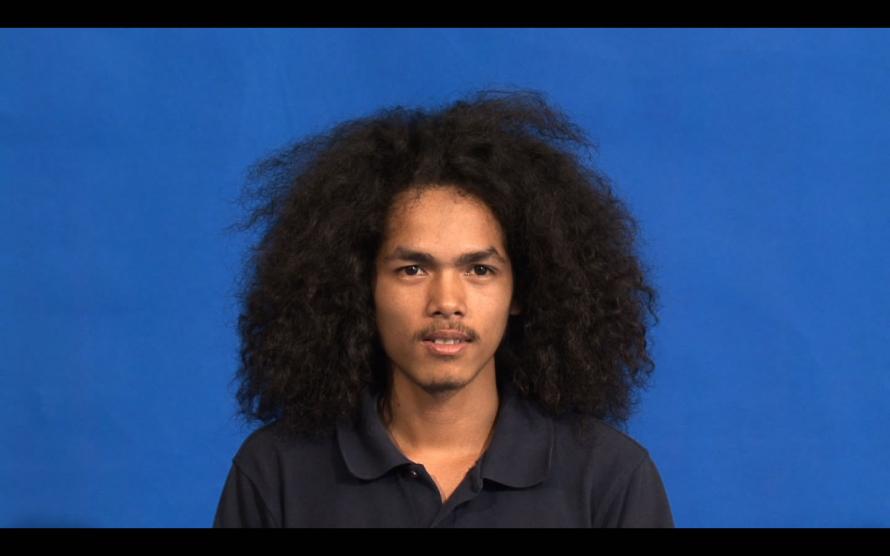

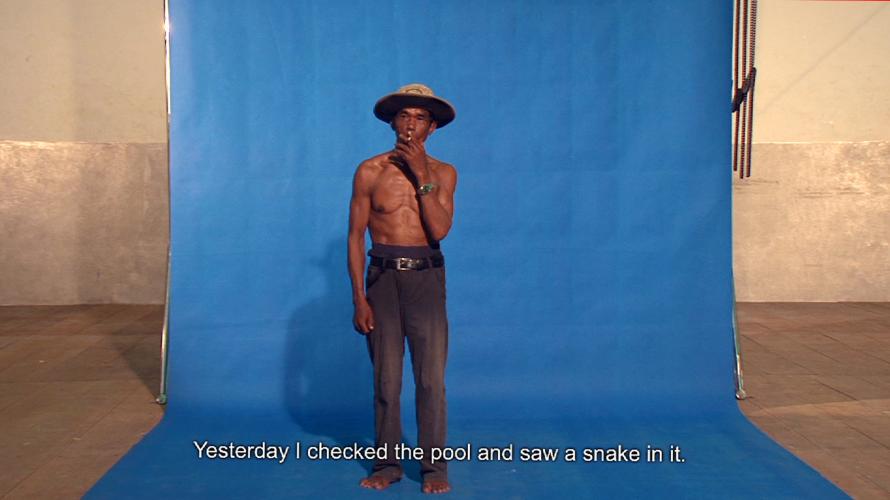

Laub started developing his Portrait Series over ten years ago. The principle sounds simple enough: a paper backdrop, much like you would see in a photographer’s studio, is unrolled, a series of people come onto the stage and perform – or just tell – their story. And everything that is extraordinary about them becomes visible with no conscious effort to produce art. They’re people like stage hands or dancers, with the kind of faces you see every day. Laub has tried out his concept in Hamburg, Berlin, Rotterdam, Istanbul and Vienna. In Battambang there was one thing he knew immediately: “I can’t send these people on tour through Europe. Even the trip to Phnom Penh would be too much for most of them.” And that’s why his Portrait Series Battambang only exists in the form of video footage.

Among those who appear on stage are a night watchman who suffered under Pol Pot, a sex worker with a nervous giggle, and a garbage-collecting girl who dreams of a career in modeling. Many young Cambodians have dreams like that, Laub says. Not because they want to be famous, but because it would enable them to support their families.

Srey Channthy is another one who knows a thing or two about poverty. She comes from a village without running water or electricity, two of her siblings died of starvation, she was taken out of school after three years. Even today she writes in a script comprehensible only to herself. It must have been quite a moment when she and her band, The Cambodian Space Project, arrived back in her village to give a concert. Her mother always hoped to see her on TV one day, says Channthy with a smile. Khmer is the only language she speaks, more or less, and an interpreter is by her side. Her path through life could easily be reduced to a hackneyed, if somewhat offbeat, tale of rags to riches. A country girl who makes good. Who consults, at one point on her path to success, a clairvoyant who is also a deserter from the Israeli Army. While singing in a karaoke bar, she is discovered by the Australian guitarist and singer Julien Poulson. After the founding of The Cambodian Space Project in 2009, international tours begin. The band was once introduced to Nick Cave after a concert; they hadn’t got a clue who the weird guy was.

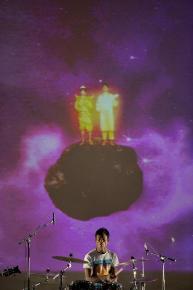

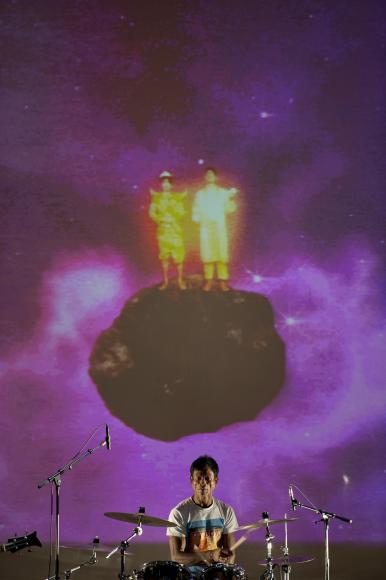

The music of The Cambodian Space Project is inspired by 1960s’ Cambodian rock, a wild mixture of styles in which the psychedelic predominates. There’s been something of a revival in recent years. Michael Laub intends to stage the band’s Berlin concert as a galactic extravaganza with additional musicians and dancers from Battambang and Phnomh Penh, optically driven by the visuals of the artist Marc Eberle. It promises to be a circus and a spectacle. “Everything except exoticism” – that was Michael Laub’s motto for the entire project.

“In the bar where I met Srey Channthy, she was singing Peggy Lee’s ‘Johnny Guitar’ in Khmer,” recalls Poulson, the initiator of the band. “I grew up with these songs,” says Channthy. Poulson mentions a photograph he saw in her village. Taken in the 1970s, it showed Srey as a little girl in shorts next to her father in his army uniform. There was a transistor radio between them – and a huge tank looming up behind them.

Franziska Buhre, Deutschlandfunk, Kultur Heute, 18.01.2014

"Staging Cambodia" Festival A Soulful Community

“Galaxy Khmer” is the name of a joint project by Belgian director-choreographer Michael Laub and the Cambodian band The Cambodian Space Project. which was presented at HAU theatre in Berlin. The fresh artistic wind blowing in Cambodia was vividly presented live on stage and in videos.

“The singer Pan Ron is my role model. She sang songs that were sexy, songs that were sometimes very fast and also funny – just lovely, all of them. Pan Ron died under the Pol Pot regime, but Pol Pot could not kill her songs. They remain in our hearts, and in those of the generation to come.”

Srey Thy, front woman of The Cambodian Space Project, has found her role in life. Since 2009, together with Australian guitarist Julien Poulson, she has been living out a shared passion for 1960s’ Cambodian rock-’n’-roll.

During that decade the music of Jimi Hendrix, the Kinks, Ike and Tina Turner, and Motown reached Cambodia via the airwaves of US army radio stations broadcasting from Vietnam. Michael Laub heard Srey Thy singing in a bar in Phnom Penh, and decided to join forces with The Cambodian Space Project to realize a performance entitled “Galaxy Khmer”, which now premiered in Europe at Hebbel Theater am Ufer (HAU) in Berlin.

Painting, Music, Dance, Drama, and Circus

Laub devotes the first part of the evening to his new Portrait Series, presented in the form of video for the first time. The new series came about with the assistance of PPS, a Battambang-based non-governmental organization that offers children and young adults schooling and training in painting, music, dance, drama, and circus performance. On a blue surface we see young girls recounting their dreams of becoming models, the PPS dance teacher who stands on one leg majestically fluttering two fans, the stranded American Nick, who’s been working on his comic book for the past five years, or an elderly man who barely survived the Khmer Rouge regime, and is now driven to desperation by his worries about looking after the three orphaned children of his brother, who died of AIDS along with his wife.

Five women talk about their experiences with violence. One after the other, they start to cry – a scene choreographed by Laub that does not expose the women; instead, it shows their dignity, and their sense of humour as well.

Three young women in little black dresses and high heels join Srey Thy on stage during The Cambodian Space Project’s concert. They dance the twist, gyrate their hips a little, sway to the right and then to the left – like ’60s background dancers, only now they’re the ones in the spotlight.

Soulful Community

It is a touching moment when one of the dancers kicks off her high heels to dance the classical Khmer dance barefoot. With majestic leisure she articulates her legs, moves her hands in wonderful gestures, tilting her head to the side. Whatever the differences in ages and backgrounds, it is clear that the band and the musicians and dancers from Battambang have formed a soulful community.

The German documentary filmmaker Marc Ebele shows footage of singer Srey Thy learning how to dance the twist from Dy Saveth, a film star who escaped the clutches of the Khmer Rouge only by fleeing to France.

Forwards – tip, backwards – tip, sway your hips while doing so and rhythmically shake your arms in front of the body. Eberle’s film about The Cambodian Space Project deserves to be seen by a lot of people. And one hopes for Srey Thy, at present only a hairsbreadth away from the bitter fates faced by other women in her country, that she will permanently widen this gap to the breadth of a river.

Joost Ramaer, Trouw 21.01.2014

Shocking life stories that speak for themselves

Theatre maker Michael Laub stages ‘portraits’ with a mix of actors and amateurs who tell a story from their lives. The latest edition offers an image of Cambodia, simultaneously shocking, moving and hilarious. “He just kept on talking, even in pitch darkness.”

Mav Veng is a Cambodian of around fifty years old. Timidly he enters the stage, in front of a big roll of coloured paper, of the kind used as a background in fashion photography. Haltingly, in constant tears, his face grimaced by grief, he tells the story of his life. How he has been chased by war, terror and poverty, from his earliest youth onwards. Repeatedly he became separated from his family – first by an American bombardment, later during the forced evacuation of his home city Battambang by the Khmer Rouge. Each time he managed to rejoin his family members, each time he survived. How and why is something Veng simply cannot fathom. Once a Khmer Rouge-soldier, of all people, held him away from an area infested with landmines where he, crazy with thirst, wanted to search for water. Before his eyes the soldier stepped on a mine himself, and lost both his legs. Veng had to carry his gravely injured enemy-saviour to safety.

Cut! Over to Phat Samnang, a young, tanned and muscular Cambodian, who first plays a swinging little tune on his smartphone and then tells about his successful career as a fashion model. What attracted him to that world was the good looks of its members. “I don’t now any fat models.”

Welcome to Portrait Series Battambang, the last of seven such theatrical portraits by Michael Laub, a French-speaking Belgian theatre maker who has made the genre into one of his specialities. Like in all previous editions Battambang’s cast is a mix of professional actors and people who have never been on stage before. Thirty-eight Cambodians, to be precise – more than twice the number of people as he used in the earlier portraits. In front of the coloured paper they tell a story, perform an act or gaze silently at their audience while their text is projected behind them. Taken from their own lives, ten minutes max. The result is a series of insights in individual lives that, shown together, also offer a bigger story – in the case of Battambang that of a poor country coming to terms with a gruesome past. In terms of content, too, the show offers a mix full of contrasts: the traumas of the elder like Veng versus the dreams and optimism of the younger like Samnang, who were born after the time of war and terror.

Battambang had its world opening on Thursday January 16 in the Berlin theatre Hebbel am Ufer (HAU). The show was staged twice there, in a double bill with The Cambodian Space Project, a band that has revived a unique Cambodian musical tradition. During the rock ’n’ roll war in Vietnam Cambodia was the only country in South-East Asia where singers and musicians made their own version of the music brought to the continent by the American soldiers. The result was a lively scene in this home-made rock, that had its heyday between 1960 and 1970. The protagonists of this genre, who had reached a star status in Cambodia, were exterminated by the Khmer Rouge, as was their music – just like classical Cambodian dance, reminiscent of Balinese dancing. The double bill formed the core of a four-day event with which HAU celebrated the nascent revival of arts and culture in Cambodia. Michael Laub also provided a special staging of the performance of The Cambodian Space Project. He inserted a classical dance, and had images projected behind the band of the murdered Cambodian rock stars.

In almost all his portraits Laub presents people who share ties with a city: the actors and other employees of the Deutsche Schauspielhaus in Hamburg (2002, the first instalment) and the Viennese Burgtheater (2011), professional dancers in Berlin (2007), ordinary Rotterdammers and women from Istanbul (both in 2010). Portrait Series Rotterdam was produced by the Rotterdamse Schouwburg for De Keuze, its annual festival of international avantgarde theatre. The Flemish Annemie Vanackere, at the time programmer of De Keuze, subsequently became artistic director of HAU in 2012. It was she who enabled the production of Battambang, financially and management-wise. All other portraits were performed live. Battambang is staged as a film. “It was the only solution”, Laub tells in the lobby of his Berlin hotel, at a highly symbolical location nearby Topographie des Terrors, the monument for the state terror exercised by the Nazis as well as the GDR. “Almost all my players care for and maintain their dirt-poor and often very sick relatives. For them it is already a problem to travel to Pnom Penh. Let alone to Europe.”

That handicap proves to be of no real consequence: Battambang leaves its audience with the feeling of just having watched a live show. It fits Laub’s oeuvre anyway. In all his portraits he makes liberal use of video. Laub may not be a filmmaker himself, but he brings a great erudition on film and literature. This he applies to what he perceives to be his mission: “Deconstructing theatre”. In his words “a trashy art form”, burdened by useless conventions. I saw him at work during the preparation of his Viennese Burgporträts.

In the canteen of the Burgtheater he engaged in a chat with Roland Koch, a star of the German-language theatre whom Laub admires, as an actor and as a person. Koch had just ended a rehearsal of Bertolt Brecht’s Die heilige Johanna der Slachtöfe. He was still wearing his fake belly, fake whig and fake glasses. This sight depressed Laub no end. “The media they use here are so obsolete”, he said after Koch had left. “And the influence on the actors is enormous. For my Portrait Series Istanbul almost all candidates brought films, photos and cd’s. And I’m talking about women who mostly grew up in primitive Turkish villages. Here in Vienna not a single actor carried modern media to my auditions.”

As with all his portraits coincidence played an important part in the coming about of Battambang. Since the late nineties he has been a regular visitor of Cambodia. Initially, he was attracted by the Pnom Penh nightlife – Laub (1953) is a child of the sixties and seventies. “In those days you had bars there modelled entirely after Apocalypse Now. The barmen and their patrons dressed and behaved like the characters in that great movie. I loved that. Alas, this Pnom Penh has now disappeared.” A few years ago he learned about a theatre school and social centre in Battambang called Phare Ponleu Selpak (PPS).

At first Laub wanted to do a workshop at PPS. He put up his roll of paper and saw the people flock from the nearby villages to tell their stories before his eyes. “Most of them did so crying, in a language I could not understand a word of”, he recalls. “And the most astonishing thing was: they kept going at it, and kept crying as well.” During Mav Veng’s turn on stage a black-out occurred, as often happens in Cambodia. “But he just went on talking, even in pitch darkness.” That is how the idea for a new portrait came up: driven by the eagerness of the Cambodians to finally relieve their souls in front of somebody who would really listen to them.

Laub is very good at listening. He is a perfectionist, who, together with a small group of trusted associates, sweats endlessly over dramaturgy, lighting and soundtrack. From the sponsors of his portraits he demands at least six weeks of preparation – an expensive eternity in theatre. But that long period also serves his respect for his players. With Mav Veng, he left it to a take in one. “We thought it irresponsible to have him go through his ordeal over and over again.” But for another memorable scene, Laub made five of his women repeat their grievous stories one more time – together, weeping and speaking simultaneously. “What the audience gets to see may have been the 15th or 16th take, I’ve lost count long ago.” The women were comfortable with that. “They worked very hard to get it right.”

Had it been otherwise, Laub wouldn’t even have asked them. “My players decide what they want to show. I will never frame anybody.” Especially the women in Battambang are often very blunt about the people they share their daily lives with. They speak openly about the suffocating conformism of their fellow villagers. And about the physical abuse and neglect they suffer from their alcoholic husbands. Before the public release of Battambang, Laub showed the film to his cast. “I asked them: do you really want your friends and families to see all this?” O yes, they did. “Are you mad!”, one of them exclaimed. “They háve to see it!”

From this patient and scrupulous approach Laub’s theatrical portraits derive their power. That is also what attracts Annemie Vanackere to his work. “The ethics of his esthetics”, as she calls it. Laub leaves shocking life stories to speak for themselves, without hyping them up, and alternates them with more lightfooted episodes, that can be moving and hilarious at the same time. Like the ten-year old girl who sings a little song in Battambang, to the tunes of Father Jacob:

“Water mèlon, water mèlon,

Papayáá, papayáá,

Bananananana, bananananana,

Fruit saláád, fruit saláád.”

Nagel, Jungle World, Nr. 5, 30.01.2014

Whisky Cambodia

Rock’n’roll in the theatre: the Cambodian band Band The Cambodian Space Project plays its first concert in Germany. The singer’s life images social conditions in her country.

They don’t believe in rushing things. A full six minutes elapse before the chord change in “Whisky Cambodia”, but then the band unleashes a psychedelic wall of sound. It’s not hard to imagine what the effect would be if you were in a crowded bar in sultry Phnom Penh, enjoying a drink and a cigarette, and not watching the band from a theatre seat in wintry Berlin.

The Belgian artist Michael Laub orchestrated the “Staging Cambodia” festival in Berlin’s Hebbel am Ufer (HAU) theatre, and presented a composition of film, photography, dance-performance and music. Laub is a choreographer and theatre director – and fortunately has no ambition to blend the diverse elements of his festival into one musical-like paste. Except for music and dance, everything is simply allowed to take place alongside each other.

Portrait Series: Battambang comes after the presentation of a video and diverse photographs by the young artist Kvay Sam-nang. Speakers in Michael Laub’s 90-minute film include peasants and watchmen, vegetable-sellers and sex workers, young circus artistes and British expats. One feels briefly anxious about the danger of being turned into a paternalistic voyeur of personal misfortune, but the film soon proves to be an impressive and humorous portrait of highly diverse inhabitants of Cambodia’s third-largest city.

And then: rock-’n’-roll in the theatre. “Normally we play in bars and clubs, or outside on the street or at parties. And a set can easily last three hours,” says Julien Poulson in an interview. Along with the singer Srey Channthy, the guitarist forms the core of The Cambodian Space Project, which the members see as an open collective rather a band with a fixed line-up. Today, the four-strong band is supported by three musicians from the Phare Ponleu Selpak Association. The NGO was founded in 1994 by young refugees aiming to offer a potential livelihood to children and youngsters, and their families as well, by training them as visual artists, musicians, dancers or circus artistes. Michael Laub’s film was made on the premises of the association.

“I like the high degree of distortion in the music of The Cambodian Space Project. To bring them together with the Phare musicians was a decision based on aesthetic considerations,” says Michael Laub. “I know it’s a real challenge for the band to play in front of a seated audience.”

“Whisky Cambodia” is the title track of the third The Cambodian Space Project album, which is due for release on 1 May 2014. Its predecessors were 2011: A Space Odyssey (2011) and Not Easy Rock and Roll (2012). The forthcoming album was produced in Detroit by Dennis Coffey, the former guitarist of the legendary Motown session band The Funk Brothers. So is the history of the band a rags-to-riches tale?

Srey Channthy was born in 1980, part of the baby boom that set in after the demise of the Khmer Rouge regime. Her village in Prey Veng, one of the poorest Cambodian provinces, lies close to the border with Vietnam. The region suffered particularly heavy bombardment during the attacks Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger ordered against neutral Cambodia in violation of international law. As a child Channthy worked in the rice fields, later in an india-rubber plantation. Her schooling ended after three years, after which the teenager went to Phnom Penh to earn money for herself and her family. Lured with the promise of a job in a beauty salon, she was abducted and taken to the red-light district. She spent a day tied to a bed with power cables until a woman outside on the street heard her screams and set her free. She finally found a job as a karaoke singer in the bars of Phnom Penh. It was in one such bar that she met Julien Poulson in 2009. “She was singing a Khmer version of Peggy Lee’s ‘Johnny Guitar’, her voice impressed me,” says Poulson. The media producer from Tasmania had recently arrived from East Timor, where he was preparing a music project funded by the Australian organization Asialink. The renewed outbreak of unrest put paid to his plan, but since the funds had already been cleared, he decided to go to Cambodia and realize a project there. “My idea of Cambodia was essentially based on the song ‘Holidays in Cambodia’ by the Dead Kennedys and the film Apocalypse Now. But I quickly discovered that before Pol Pot came along there was a thriving Cambodian film, art and music scene.”

Within days of the invasion of the Khmer Rouge in 1975, Phnom Penh was evacuated. The residents were forced to set off on long marches to rural areas. During the three-and-a-half years of “Democratic Kampuchea” under the Khmer Rouge, almost two million citizens died.

As well as Buddhist monks and supporters of the right-wing Lon-Nol government, artists and intellectuals were among the new regime’s first victims, being considered incompatible with the concept of an ultranationalist peasant Maoist state. Because it was necessary to preserve ammunition stocks for the battle against the advancing Vietnamese troops, many were killed with blunt objects in the “killing fields” then dumped in mass graves. Others were worked to death in the paddy fields, or died of starvation. Many works of art, rolls of film and reels of tape were destroyed.

“They could kill the musicians, but not the music,” says Srey Channthy. “At home my mother always sang the songs from the sixties and seventies. When I met Julien, I couldn’t believe that a foreigner knew these songs and could even play them.”

“I had scoured Phnom Penh for contemporary Cambodian music. Weddings were the best source,” Poulson relates. “You’d hear a lot of the old Khmer pop songs at the celebrations. I collected recordings, and after I’d heard Channthy singing, I played her the songs on my laptop. She only had a smattering of English, and I didn’t speak Khmer at all, but though we could scarcely talk we got on immediately.” Five months later, he moved to Phnom Penh and began working with the band. They rehearsed three sons and played their first concert in a restaurant called Alley Cat Café. They had to play their short set four times over. “Channthy’s a born entertainer. In the space of a few performances she’d become a real pop diva up on the stage.”

“It took me a few months even to pronounce the name of the band,” laughs Srey Channthy. From that point on, the band appeared not only in the capital’s bars and clubs but also played in the countryside, for instance in the singer’s home village. “Whisky Cambodia” is about the celebration there, the festive meal and the rice brandy that flowed in copious amounts.

When her family heard that the band was booked to play a concert in Hong-Kong, they were afraid that the “barangs” – the foreigners in her band – would sell off Srey Channthy while overseas. Unjustified though the fears were in this case, they were hardly surprising. Young Cambodians of either sex continue to be abducted, or sold by their families, into virtual slavery in Cambodia or abroad as house-servants, wood collectors, sex workers, or street beggars.

The classics from the golden age of Khmer pop account for a large part of the albums and concerts of The Cambodian Space Project. For instance, “Chnam Oun Dop-Pram Muy” (“I am 16”) by Ros Sereysothea, which the band delivers in a wild up-tempo surf version. “I love that song, it’s sexy and funny!” says Srey Channthy, and Julien Poulson adds that it’s meanwhile become “something like the unofficial national anthem of Cambodia”.

Ros Sereysothea was considered the “golden voice of Phnom Penh”. When the city fell to the Khmer Rouge, she was forced to marry “Brother number one”, a high-ranking adjunct of Pol Pot. Nothing more was heard of her after 1979, she was very likely murdered.

The band’s 2010 single “I’m Unsatisfied” (originally “Kynom Mon Sot Jet Tai” by the singer Pan Ron) was the first vinyl release by a Cambodian band since 1975. Apart from the “Cambodian Elvis” Sinn Sisamouth, who accompanied King Sihanouk on his travels in the 1970s, Srey Channthy is the first Cambodian artist to present her music on stages around the world. The band has already toured most of Southeast Asia as well as China, Australia, the USA and Europe. “When I showed my village the photos of our trip to Paris, people didn’t believe me,” says Srey Channthy. “They thought they were looking at faked images. My family’s now proud that I’m able to travel and earn good money at the same time.” While many western musicians talk at great length about realizing their potential and DIY and like to talk up the “independence” of their precarious existence, Srey Channthy makes no bones about the delight she feels in being able to live from her music and support her family as well.

In Phnom Penh the singer runs a shop called Sticky Fingers that sells records, CDS, and its own T-shirts screen-printed in the band’s signature sci-fi and Pop Art style. Together with Kong Nay she recorded the EP 3 Songs for Human Rights. Because the blind zither player was forced to record propaganda songs for the Khmer Rouge in the late ’70s, he was one of the few musicians to survive Pol Pot’s regime. Also forthcoming this year is Srey Channthy’s collaborative recording with the Australian hip-hoppers Astronomy Class. Some months ago she was granted an Australian residence permit, a document that will greatly facilitate her ability to tour and work with the band.

The song “Have Visa, No Have Rice” conveys her ironic take on the problems (western food among them) she experiences when travelling. In other songs like “The Boat” or “Black to Gold” she talks about poverty and corruption. But Srey Channthy prefers not to make explicit political statements, saying that her songs have room for precisely three moods: “happy, sad and funny”.

The music of The Cambodian Space Project is inspired by different sounds of the 1960s and ’70s: rock ’n’ roll, pop, garage, surf, psychedelic. The old Khmer rock bands were already influenced by the US rock and pop that entered the country via the radio stations broadcasting to the GIs stationed in South Vietnam. During the HAU concert, for instance, they played a highly idiosyncratic version of “Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down)”, which was written by Sony Bono in 1966, first sung by Cher, covered by Nancy Sinatra, and gained a new lease of life in Quentin Tarantino’s 2003 film Kill Bill. In Cambodia the song is primarily known as “Snae Ha”, which is the title of Pan Ron’s adaptation.

The familiarity of the music may have been disappointing to those who visited the HAU theatre expecting an exotic world-music adventure. What we saw on the stage was a rock band from Cambodia as opposed to a Cambodian band.

As well as the phonetics of the singing and the dancehall rhythms of the percussionists, it was the two traditional instruments, of all things, that gave the songs a very modern touch. The roneat (xylophone) and the khim (a kind of cymbal) were played by the two musicians from Phare, and the results were sometimes reminiscent of the patterns of electronic music.

The first words from the band came just before the encore: in broken English Srey Channthy asked the audience to come up and dance on the stage. But the Berliners stayed seated. Maybe they felt like I did: it would be great to have an opportunity to see this band at a crowded, sweaty party in Phnom Penh – and to enjoy a drink and a cigarette at the same time.

Norsk Shakespeare og Teater Tidsskrift

Issue 1 / 2014

Pop and Pol Pot. Michael Laub’s The Cambodian Space Project: Between tears and optimism, classical Asian ballet and extravaganza.

By Knut Ove Arntzen MICHAEL LAUB THE CAMBODIAN SPACE PROJECT.

Portrait Series Battambang / Galaxy Khmer, Concept and directing: Michael Laub. Music by: The Cambodian Space Project with Srey Channty and Julien Poulson, Dancers from The Royal Ballet in Phnom Penh. Film animations by Marc Eberle / Tim Huys Co-production BIT Teatergarasjen, Hebbel an Ufer Berlin and Phare Ponleu Selpak Association. Studio Bergen, BIT Teatergarasjen, 23 -24 January.

The Belgian Michael Laub began making video art along with Edomondo Za in 1975, and from 1981 on he was running the Scandinavian theatre project Remote Control Production in Stockholm, where he had obtained support from Moderna Museet. His productions gained meagre attention in Sweden, since working with models and showing euro trash - violent scenes based on crime films and diary notes was regarded as not being politically correct. In Norway, he got in contact with Bergen Internasjonale Teater, who in 1989 presented Rewind Song in the old tram rail hall at Møhlenpris. This production became a success among the festival spectators, and more Remote Control Productions’ shows were produced throughout the 1990s. Programmers from the Netherlands and Belgium had come to Bergen to see Laub’s company among other productions, and in a way this led him artistically home. Belgium is Laub’s native country. He felt more as a stranger in Sweden, where resistance to trash-aesthetics and cabaret dramaturgy existed but was perceived by him as something constructive. One of the models he worked with in Sweden, Lotta Engelkes, began to make solo productions in cooperation with Michael Laub. Gradually he moved his productions over to the Netherlands and Germany, and still for some projects with BIT Teatergarasjen as co-producers.

One of the last productions he showed in Sweden at the end of the 1990s was Planet Lulu, based on Frank Wedekinds Lulu-plays from 1997. This production was a cooperation between him and the performance artist Marina Abramovic who made the scenography. After this came his solos and finally his Portrait Series, put up in Hamburg, Istanbul and Vienna. The series was initiated about ten years ago and focused on portraying and putting on stage ordinary people, or, like at the Burgtheater in Vienna in 2011, stage workers, ticket salesmen and stage technicians. This was no simple process but it was completed in spite of a lot of conflicts.

Portrait Series Battambang / Galaxy Khmer

Earlier Michael Laub had taken interest in South and South-East Asia with video works from Bangkok and productions like Total Masala Slammer in 2001, based on Indian material. More than ten years later he travelled to Cambodia where he quite surprisingly came upon some people and a material that made him create a new production within his Portrait Series: MICHAEL LAUB THE CAMBODIAN SPACE PROJECT. Portrait Series Battambang / Galaxy Khmer. This is a film show and a production that is developed in cooperation with the Rock group The Cambodian Space Project and also in cooperation with the German movie director Marc Eberle, who lives in Cambodia. The site of production is a culture park in the Battambang province called Phare Ponleu Selpak Association; it is not run by public government but aims at developing local culture and identity through workshops and circus schools. Laub arranged a workshop with different people in Battambang who all have their own personal history to tell either connected to the civil war and genocide in Cambodia during Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge or the more optimistic stories of young amateur artists and wannabes. They all perform their solo presentations as storytelling or as a kind of dance and drama show. These were then filmed and make the basis of the first part of the production, which lasts about 70 minutes. These are all moving stories containing a lot of tears but also laughter, depending of which of the generations the stories belong to and how close they were to ‘The Killing Fields’, that is, the fields where about one and a half million people were tortured and killed by the Khmer Rouge when they took the power in 1975. The young generation has another optimism and perspective on life than the old, and this has a powerful impact on the portraits that were showed in these filmed and photographic portraits cast by Ebru Karaca. What is particularly fascinating by these portraits is the theatrical consciousness that is expressed by many of the portrait subjects in their tableau-like attitude shows. However, the contrast between the two generations is huge and I suppose the material touches the spectators in different manners both emotionally and intellectually. The fact that these portraits were shown as film probably made them more distanced and easier to digest than if they had been cast as live-performances.

Classical culture, pop-culture and extravaganza-shows

The rock music that Cambodian Space Project Galaxy is producing and that was used in the second part of the show was a part of an hour long, sparkling extravaganza show with focus on the singer Srey Channty.

The extravaganza show as such is an Asian phenomenon that is also known from Thailand. It is a blend of different elements such as pop music, folk music and classical Asian dance it is really even a type of show where you eat while watching, something that sadly was no part of this show.

Its historical background is that during the 1960s the Cambodian King Prince Shianouk as text producer and musician was in charge of a flourishing entertainment and music life with elements of American Ray Charlton dance, something which is well documented in the archive files that Mark Eberle has been working with in order to produce his animation films, where he is even working with lotus motifs and with extracts from romantic films of the time. This then, is the background of the show and rock concert, which even include dancers from the Cambodian Royal ballet in Phnom Penh. The ballet was almost eradicated during the Khmer Rouge period, and only a few, if not only one dancer survived. This dancer later contributed to the revival of this more than a thousand year old Cambodian dance tradition. It looks a little like Thai temple dances, and is working with grace and body control in figurative direction, with special emphasis on hand- and finger movements. These dancers perform in black, elegant dresses and a transformation between classical techniques and pop and rock music is taking place. We are also shown a stage show with the same dancers in its traditional costumes and head attire.

In Asia people have never been afraid of mixing high and low culture, due to the fact that here they have not had the European romantic focus on the authenticity of the form. The Asian dance traditions became a powerful source of inspiration to Eugenio Barba of Odin Teateret as well as to other artists, and the figurativeness and body work had been imported from the Theatre Laboratory groups of the 1960s and had been transformed into the more postmodern and deconstructed expression forms of postmodern or post-dramatic theatre groups like Baktruppen and Michael Laub’s Remote Control Productions. Even here dance played an important part, and in a way this represents a full circle that is finished in MICHAEL LAUB THE CAMBODIAN SPACE PROJECT Portrait Series Battanbang / Galaxy Khmer. Here too dance constituted an important part. We are faced with – and are shown – a globalized theatre, globalised art and contemporarily a political nerve strikes into this work. This nerve may be talked of as post-genocidal and touches on our relationship to an uprising against and memory of atrocities that were inspired and ignited by European ideas in cooperation with the American warfare in South-East Asia and the cluster bombing of Cambodia that helped the Khmer Rouge into power. But in this mixture of Western pop culture and Classical Cambodian dance lies the chime of forgiving. And Michael Laub was not so very politically incorrect, at least not in this production.

Translation by: Anna Fransisca Helleland