Michael Laub / Remote Control Productions

Maniac Productions (1975–1979)

PHOTOGRAPHY / VIDEO / PRESS

PRESS

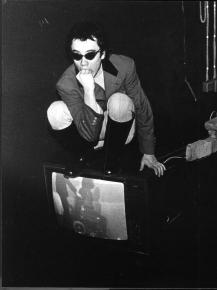

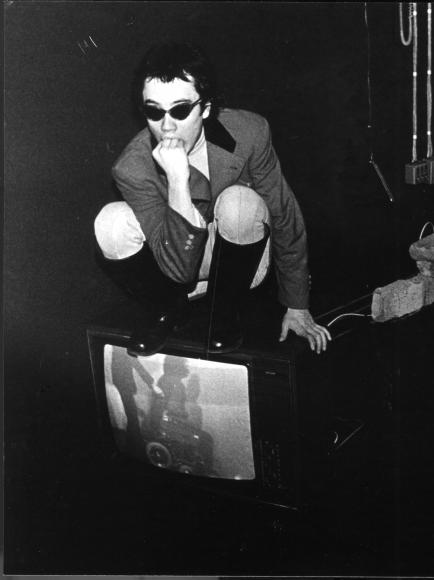

Genevieve van Cauwenberg, Video Belgium, 1978

From Maniac Productions to Remote Control

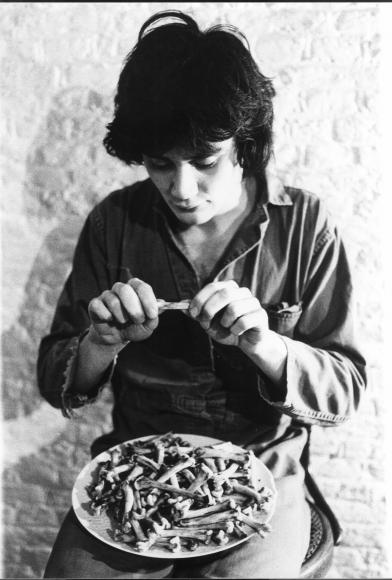

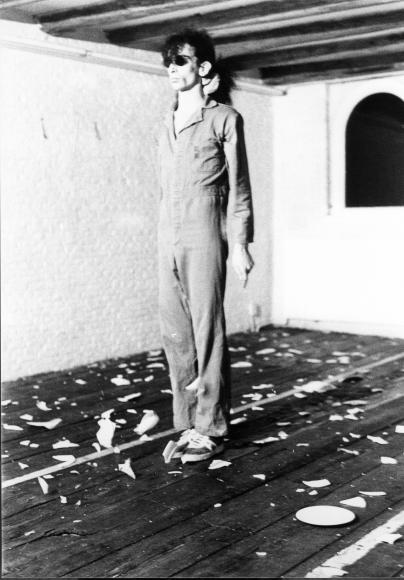

Maniac Productions is the small group of performing artists that Michael Laub (Belgian) and Edmondo Za (Italian) set up in October 1975. A cosmopolitan group with variable geometry (four members at present), it performs in the shrines of the European avant-garde and is based in Stockholm. The performances of Maniac Productions, which Italian critics often term ‘theatrical post avant-garde’, are in fact polyvalent and difficult to classify. They make use of everything at once, combining their specific language, stage direction, plastic arts (Minimal Art), musical composition (repetitive: Steve Reich), body language (Body Art), Happening (intervention of hazard) and of course the electronic video image. Maniac compounds these elements into something resembling fragments of a new ‘theatrical’ language that they refuse to articulate, and produces ‘spectacles’ that abound with dissonances. First they worked with repetition and fragment – early productions consisted in a series of cut-up sequences, put side-by-side, built on mechanical renewal and systematic reiteration (of words, movements and gestures). This repetitive structure was present in the strictest frigidity: cool performances, even XXX icy; the actors functioned like abstract performing machinery. Dissatisfied with this strict use of repetition, however, Maniac decided to produce ‘failures’ within the too well-adjusted machinery: stops, blanks, silences, gaps, doubts, hesitations, irresoluteness. So many moments where something could happen, extend beyond the impersonal mechanism, so many potential points of emergence for uncertainty and individuality. The actor as such returned to the individual. Through these cracks enacted in the course of repetitive actions, the acting ungovernableness developed. And it’s still growing in the present evolution of the group’s performances. Repetition most certainly stays as an active principle: every character remains the prisoner of his own doings but then, setting traps for himself, lets himself fall into, be caught inside, them. The hallucination becomes hallucinatory. The ‘analytical’ effects of the mechanism are amplified. Performance therapy. Obsessive and unconscious repetition. Anxiety is always about to arise. Controlled hysteria and lucid madness. A multiple role is also played by the insertion of video into the performance mechanism. Juxtaposed with the action, video enables the simultaneous production and consumption of the image in a single space. It has the structural function of injecting distance: there is what happens in a space where an action is taking place, and what happens on the screen that bears witness. Various relationships (contrast, analogy). The presence of the monitors means work can take place both on a spatial and temporal plane: television is presented either as a window that commands a view of the outer world, beyond the theatrical space, or as a mirror reflecting the internal mechanism of the action. The TV screen can show what has happened and what is going to happen. Temporal shifts can produce a whole range of disorders. Well-ordered, well-located, rolling-by time now suffers all the outrages of destruction. A time of forgetfulness is established, just as with repetition. Dislocation of language. Destruction of time. Rupture of space. Weathering. Dispersion. Fissure. Cracks. Gaping. A whole universe in dislocation, sliding towards its loss and absence. Nothingness.

Marina Abramovic, January 2000

A Personal Statement

It was the 1970s and everything seemed to be possible. Nobody believed in old structures. It was the time of big changes in music, in art, in theatre. Bergman, Godard, Antonioni were still significant. But that was not enough. We were feeling the twilight of all ideologies. At the time, Ulay and I were travelling around Europe in an old Citroen bought from the French police. The only reference point where we could collect our mail was the Appel Gallery, then the most avant-garde place that regularly presented Performance art. So, we were sitting in the Apple when the postman arrived with a package from Sweden. The address of the sender was incomplete – merely Maniac Productions, Stockholm. In those days, videos were quite rare. Together with the people from the Appel, we immediately looked at the tape. It was a review of short performances with three people involved. What we saw stayed a long time in our memory: it was fresh, disturbing, had a touch of strangeness. Time passed by, Ulay and myself continued to tour Europe, and almost a year later again found ourselves in the Appel. The door opened and three people entered the space: a short man with piercing eyes followed by a girl dressed completely in white. Around her neck was a toilet seat she wore as proudly as precious jewellery. The last to enter was a tall, skinny man who looked like a rock’n’roll star. Immediately, everybody in the room knew that Maniac Productions had come to town. For me it was the beginning of long-lasting friendship, co-operation, and deep understanding. Maniac Productions later fell apart, and Michael started up the new Remote Control Productions. The work and approaches to theatre changed and became more obsessive, more elegant and at the same time blacker, more violent. What I now like about Remote Control Productions is its ability to filter and edit real-life experiences into movie-like reels of scenes. It requires viewers to take responsibility for their impressions. Travelling recently by taxi through a Bombay slum, surrounded by piles of indescribable rubbish, Michael turned to me and said, ‘Look at this reality, this is as spiritual as I get.’